What Good Politics Is For: Solidarity in an Age of Unfreedom

Most of us now experience politics not as a shared process of collective problem-solving, but as a relentless source of exhaustion, spectacle, and threat. It is the feeling of being worn down by the ceaseless torrent of breaking news alerts, each demanding our immediate and undivided attention, only to be forgotten in the next cycle. It is a machine that seems to run on our anger and our anxiety, a theatre of perpetual conflict where the script is written by the loudest and most divisive voices. Recent studies have shown that a majority of citizens in established democracies feel worn out by this constant political churn (Pew Research Center, 2023). The promise that politics could be a means to build a shared future has been inverted; it now offers a steady diet of enemies, a curated nostalgia for a past that never was, and the fleeting satisfaction of revenge. We are left with a profound and unsettling absence. We argue, with increasing bitterness, about who should rule and who should lose. We rarely ask what politics owes the human being. The answer to that question, the moral purpose that has been lost in the noise, is solidarity.

This essay is an attempt to recover a moral architecture for our political life, one built not on the shifting sands of identity or the sugar high of outrage, but on the bedrock of solidarity. This is not a call for unity, which is too often a demand for silence. It is not a celebration of identity, which can be as much a cage as a comfort. Solidarity is something quieter, more demanding, and more durable. It is the slow, difficult, and disciplined practice of standing with others, especially when it is hard. It is a recognition that our own freedom is bound up with the freedom of others, and that our own dignity is incomplete without the dignity of all. It is the conviction that while we are not all the same, we are, in the political sense, equal. Where solidarity has been practiced, however imperfectly, democracies have weathered storms. Where it has collapsed, the vacuum has been filled by the organised cruelty of unfreedom.

What Politics Is Not

Before we can ask what good politics is for, we must clear away the debris of what it has become. For many, politics is no longer a recognisable system of representation or a forum for debate. It has been drained, its substance replaced by a series of false substitutes that wear its name but betray its purpose. These are not politics; they are its opposite. They are the machinery of anti-solidarity, the tools by which citizens are isolated, atomised, and rendered powerless.

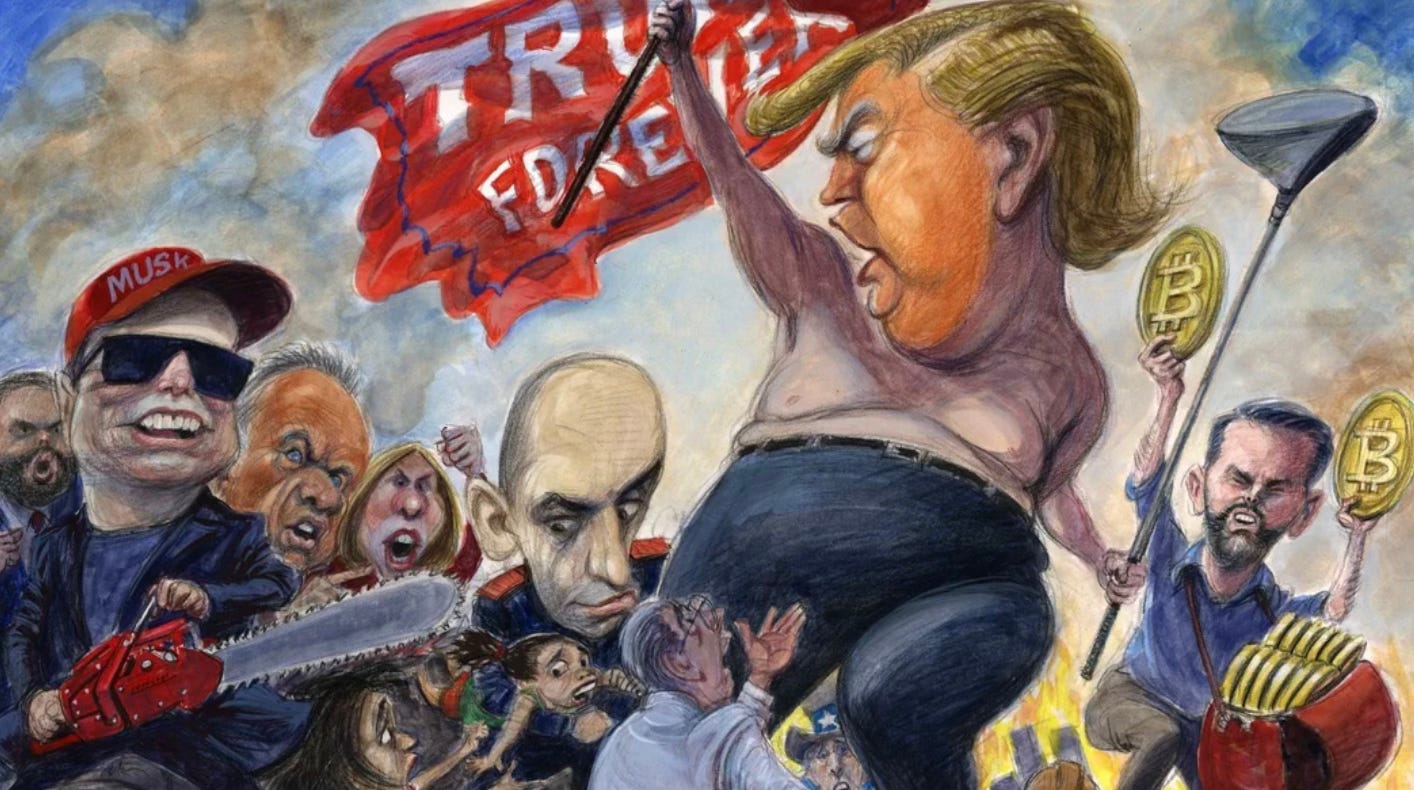

First, politics is not performance. The public square has been replaced by a permanent stage, and leaders are now rewarded not for their judgment or their foresight, but for the quality of their performance. Cruelty is applauded as strength. Volume is mistaken for authority. The humiliation of opponents is treated as a victory. In this theatre of resentment, spectacle replaces accountability (Debord, 1967). Governance is reduced to a series of calculated outrages, each designed to capture attention and provoke a reaction, leaving no space for the quiet, unglamorous work of building consensus or solving complex problems. The citizen is recast as an audience member, asked only to cheer or to boo.

Second, politics is not permanent conflict. The deliberate engineering of division has become a primary strategy of rule. An electorate permanently mobilised against a common enemy is an electorate that will not ask difficult questions of its leaders. ‘Us versus them’ is the operating system here. Conflict is a resource to be managed and sustained. This permanent state of mobilisation is corrosive. It exhausts the civic spirit, erodes the trust necessary for a functioning democracy, and leaves citizens in a constant state of anxiety and suspicion. It makes it impossible to imagine a future that is not a continuation of the present war.

Finally, politics is not emotional catharsis. In an age of anxiety, anger is sold as empowerment. Grievance is cultivated and curated until it becomes a substitute for identity. The feeling of being heard, of having one’s pain acknowledged and amplified, is offered as a replacement for the material reality of being protected. But the catharsis is fleeting. The outrage machine demands to be fed, and the brief satisfaction of seeing one’s own anger mirrored does nothing to change the underlying conditions that produced that anger in the first place. It is a transaction that benefits the powerful and leaves the citizen with nothing but the echo of their own shout.

When politics abandons its core responsibilities to manage conflict, distribute resources, and to protect the vulnerable, it becomes dangerous: a machine for manufacturing division, a platform for performative cruelty, and a tool for the powerful to distract and to disarm the public. It becomes, in short, a technology of anti-solidarity.

A Working Definition of Good Politics

If politics has been gutted by performance, conflict, and catharsis, then what is the alternative? Good politics is a moral practice, and its principles apply to the life of a nation as much as to the life of a family, a workplace, or a chance encounter with a stranger.

Good politics begins with limits. At the national level, it insists that power is a trust, not a prize. It is a system in which leaders are bound, not liberated, by the offices they hold. The law is not a tool to be wielded against enemies, but a boundary that applies to everyone, especially the powerful. The peaceful transfer of power after an election is not a sign of weakness; it is the ultimate expression of this principle. It is the moment when a leader who has held the power of the state steps aside, accepts the will of the people, and allows another to take their place. In the home, it is the parent who respects the growing autonomy of a child, who guides rather than commands, and who understands that their authority is a temporary stewardship, not a permanent possession. At work, it is the manager who does not exploit their position, who listens to their subordinates, and who accepts that their power is contingent on the consent and respect of their team. A politics without limits is the short road to tyranny.

Good politics reduces fear and offers a lifeline when you need it. It provides health when we get sick. Support when we fall, a way forward when we stumble. The ultimate measure of a political system is the extent to which it makes its citizens’ lives more secure. A citizen should fear poverty, illness, and injustice less, not more, because politics exists. Public health initiatives that eradicate diseases, or social insurance programs that protect against the uncertainties of the market, are expressions of a politics that takes fear seriously. These are not luxuries, but necessities. They are the foundation of a life lived with dignity. A loving home creates a predictable and safe environment where a child does not live in fear of abandonment or arbitrary punishment. A decent workplace reduces the fear of economic ruin, and a civil public square reduces the fear of the stranger. Good politics is a shield against the chaos of the world.

Good politics expands the circle of obligation. It constantly asks the question: who counts? Who is included in the ‘we’ of our concern? A politics of division seeks to shrink this circle, to narrow it to the tribe, the nation, the chosen few. Good politics does the opposite. It works to widen the circle of mutual responsibility, from the immediate family to the neighbour, to the stranger, to the foreigner. The civil rights movements in the U.S. that dismantled legal segregation were movements that forced the nation to live up to its own stated ideals, and in so doing, expanded the meaning of “we the people.” It is a politics that understands that a nation is not a tribe, but a shared project.

Good politics insists on equality. This is the principle that holds the others together. It is the recognition that while we are not all the same, in a just and good politics, we are all equal. We are not equal in talent, in beauty, in strength, or in virtue. But we are, or should be, equal in our dignity, in our right to be safe from harm, and in our standing before the law. This is the most radical of all political ideas. It is the idea that the life of a poor child matters as much as the life of a billionaire, that the voice of a dissident matters as much as the voice of a president, that the pain of a stranger matters as much as the pain of a brother. A politics that abandons this principle, that creates hierarchies of human worth, has already surrendered to the logic of unfreedom.

Finally, good politics protects the freedom to speak truth to power. The other pillars cannot survive without this one. Limits on power are meaningless if those who point out their violation are silenced. Fear cannot be reduced if citizens are afraid to name the sources of their fear. Equality is a fiction if some voices are amplified and others are suppressed. The freedom to speak truth to power is the immune system of a democracy, the mechanism by which a society identifies its own diseases and begins the work of healing. It requires institutional protections: a free and independent press, a judiciary that can protect critics, laws that shield whistleblowers, universities where unpopular ideas can be debated. It also requires a culture that values dissent as a sign of health, not disloyalty.

Speaking truth to power will always require courage. But good politics creates a world where that courage is not suicidal. It creates a world where the powerful have more to fear from the truth than the powerless have to fear from speaking it. Good politics does not fear dissent; it defends it. Good politics does not fear protest; it encourages it.

This is not a politics that promises greatness. It does not offer the thrill of domination or the satisfaction of seeing one’s enemies vanquished. It promises something far more valuable, and far more difficult: dignity under strain. It is a politics that is modest in its ambitions but fierce in its commitments. It is the quiet, patient, and essential work of holding a society together through the steady application of law, the determined reduction of fear, and the constant, stubborn effort to see ourselves in one another. These five pillars — limits on power, fear reduction, expanded obligation, equality, and the freedom to speak truth to power — are interconnected, each dependent on the others. Together, they form the foundation of a politics that is worthy of the name.

Subscribe to Notes From Plague Island and join our growing community of readers and thinkers.

Solidarity: The Most Misunderstood Word in Politics

Solidarity is the ghost at our political feast. The word is invoked often, but its meaning has been eroded, reduced to a sentimental slogan or a brand for a particular kind of politics. It is invoked by those who have no intention of practicing it. Solidarity is neither a feeling, nor the warm glow of belonging to a group. It is a practice. And it is the most essential concept in our political vocabulary.

Solidarity is not sameness. This is not a call for us to erase our differences and melt into a single, undifferentiated mass. The demand for unity is often a demand for conformity, a pressure to silence dissent and to pretend that our disagreements do not exist. But difference is not a weakness of a democracy; it is its source of strength. A politics of solidarity requires us to see our own fate as tied to the fate of others, even, and especially, when those others are different from us. It is the recognition that an injustice to one is a threat to all, not because we are all the same, but because we all share a common vulnerability to power and an equal claim to dignity.

Solidarity is not charity. Charity flows downward, from the powerful to the powerless, from the fortunate to the unfortunate. It is an act of benevolence, a gift given from a position of safety. Solidarity, by contrast, is horizontal. It is the act of standing beside, not above. It assumes a relationship of equals, bound together by a shared struggle. A striking worker on a picket line is not asking for charity; she is asking for solidarity. She is asking others to recognise that her struggle for a living wage and safe working conditions is their struggle too, because it is a struggle for a society in which the dignity of labour is respected. Charity can be a way of maintaining the status quo, of making an unjust system more bearable, but solidarity is a way of challenging that system.

Solidarity is reciprocal and structural. It is not a fleeting emotion, but a sustained and disciplined commitment. And that commitment cannot survive on goodwill alone. It requires institutions and systems that turn our moral obligations into concrete realities. Unions, which give workers the collective power to demand a fair share of the wealth they create. Welfare systems, which recognise that we all have a right to a basic level of security and dignity. Public education, which gives every child a chance to develop their potential. Independent courts, which ensure that the law applies to everyone, not just the weak. Without these structures, solidarity collapses into a mood, a gesture, a performance. It becomes another form of emotional catharsis, another way of feeling good about ourselves without changing anything.

Solidarity is what remains when the applause fades and the bill arrives. It is the quiet, unglamorous, and essential work of building a society where we are all responsible for one another. It is the understanding that we are not isolated individuals, but members of a community, and that our freedom is not a private possession, but a shared inheritance. It is the choice, made repeatedly, not to abandon one another. It is the agreement that we will face the future together, and that no one will be left behind.

The Historical Record: When Solidarity Worked

This is not a utopian fantasy. It is a memory. The architecture of solidarity has been built before, and its ruins are all around us. The post-war European project was not just an antifascist infrastructure built on the ashes of a continent (Eley, 1996). The creation of welfare states, the expansion of public healthcare, and the commitment to human rights were all expressions of a political choice: never again. It was a decision to build a society that was resilient to the appeal of demagogues, a society that reduced the existential fear that had made fascism possible. The welfare state was not a luxury; it was a necessity. It was the price of peace, and of ensuring that the desperation that had led to fascism would not emerge again.

Similarly, the American New Deal was a fundamental reordering of risk in American society (McCarthy, 2017). Social Security, unemployment insurance, and the right to collective bargaining were all mechanisms for socialising risk, and ensuring that the misfortunes of the market did not lead to the destitution of the individual. It was a recognition that a society that allows its citizens to fall into despair is a society that is vulnerable to the politics of despair. The New Deal was an act of solidarity, a decision that the nation would stand with those who had been abandoned by the market. It was a recognition that we are all vulnerable, and that vulnerability is not a personal failing but a human condition.

Trade unions, at their best, were schools of democracy (O’Neill and White, 2018). They were places where ordinary people learned the skills of collective action, negotiation, and compromise. They were institutions that gave workers a voice, not just in the workplace, but in the nation. A union meeting was a place where a factory worker could stand up and speak, where their voice mattered, where they were treated as an equal. The decline of unions is a story about the erosion of our civic capacity, and about the loss of spaces where ordinary people could practice democracy, learn to lead, and develop the confidence to participate in public life.

How Solidarity Was Dismantled

If solidarity was once a powerful force, how was it broken? It was not an accident but the result of a deliberate, multi-decade project of political and economic transformation. First, the rise of neoliberalism reframed the citizen as a consumer and the state as a market actor (Lorenz 2005). The language of shared risk and collective responsibility was replaced by the language of individual choice and personal responsibility. It taught us to see ourselves as competitors, rather than collaborators. The welfare state was reframed as a burden. Public goods were reframed as private responsibilities. And the language of solidarity was replaced by the language of self-reliance.

Second, as the economic basis of solidarity eroded, it was replaced by a politics of culture. The real, material conflicts over wages, working conditions, and public services were converted into symbolic battles over identity and values (Fraser, 1995). This was a brilliant and devastating manoeuvre. It divided the very people who had the most to gain from a politics of solidarity, pitting them against each other in a series of endless and unwinnable culture wars. Workers who should have been united by their shared economic interests were instead divided by their cultural identities. The result was a politics of resentment, in which people voted against their own material interests in order to punish those they perceived as cultural enemies.

Finally, the rise of social media created a new infrastructure for political life, one that was perfectly designed to amplify division and to reward performance (Levy, 2021). The algorithms that govern our online experience are not neutral. They are designed to maximize engagement, which is most easily achieved through outrage, conflict, and the constant affirmation of our own biases. We were placed in bespoke realities, our sense of a shared world fracturing with every click. The commons of shared information disappeared, replaced by a fragmented landscape of competing truths. The possibility of solidarity, which depends on a shared understanding of reality, became increasingly difficult to imagine.

Bad Politics as Anti-Solidarity Technology

Into the vacuum created by the collapse of solidarity has stepped a new and dangerous form of politics. Modern authoritarianism is not just a collection of bad policies; it is a technology of anti-solidarity. Its primary goal is to isolate the citizen, to break the bonds of trust and mutual obligation, and to leave the individual alone and afraid before the power of the state. It is the politics of loneliness, fear, and of the individual against the world.

It does this by first attacking the institutions that make solidarity possible. Independent courts, a free press, universities, and unions are all targeted, not just because they are obstacles to power, but because they are spaces where citizens can gather, organise, and develop a shared understanding of the world. These are where solidarity is forged, where people learn to see themselves as part of a larger whole. The goal is to leave the citizen with only one source of information and one object of loyalty: the leader. Isolated, atomised, and afraid, the citizen becomes malleable, easy to manipulate, easy to control.

Second, it perfects the art of permanent conflict. It identifies enemies, both internal and external, and mobilises the population in a constant state of war against them. It provides a sense of meaning and purpose in a world that has been stripped of them. But it is a meaning that is based on hatred, and a purpose that is based on destruction. The enemy is always present, always threatening, always demanding vigilance. There is no time for solidarity, no space for cooperation, no possibility of compromise. There is only the eternal struggle between us and them.

Finally, it offers a politics of pure performance. The leader is not a statesman, but a celebrity, a master of the spectacle. His rallies are rituals of collective affirmation. His words are meant to enchant. The goal is not to govern, but to reign. It is a politics that is all surface, with nothing beneath.

Solidarity in Practice: The Work of Reconstruction

If the last 40 years have been a story of dismantling, the next 40 must be a story of reconstruction. This is not a matter of finding the right leader or winning the next election. It is the slow, difficult, and unglamorous work of rebuilding the institutions and the habits of solidarity from the ground up.

This work begins with a commitment to truth. We must reject the politics of spectacle and insist on a politics of reality. This means supporting independent journalism, demanding evidence-based policy, and refusing to participate in the outrage machine.

It means rebuilding the institutions of solidarity. This is not a utopian fantasy, but a practical program grounded in what we know works.

In healthcare, it means defending and expanding public health systems that treat healthcare as a right, not a commodity. It means ensuring that no one faces bankruptcy because of illness, that preventive care is available to all, and that the profit motive does not determine who lives and who dies. It means acknowledging that a healthy population is a public good, and that the cost of healthcare should be borne collectively, not individually.

In labour, it means finding new ways for workers to organise and to bargain collectively in a globalised economy. It means making it easier for workers to form unions, banning non-compete clauses that trap workers in exploitative situations, and ensuring that workers have a voice in the decisions that affect their lives. It means recognising that workers are human beings with dignity and rights.

In housing, it means a commitment to building affordable housing and protecting tenants from the whims of the market. It means treating housing as a human right, not as a speculative asset. It means rent control, tenant protections, and a massive public investment in affordable housing construction. It means realising that a person without a home is a person without dignity.

In education, it means reinvesting in public education from early childhood through to university level. It means that a child’s life chances are not determined by their parents’ wealth. It means that education is a public good, funded publicly, and available to all. It means understanding that an educated citizenry is the foundation of a functioning democracy.

And in migration, it means creating a system that is based on law and compassion, not on cruelty and chaos. It means accepting that people have the right to seek safety and opportunity, and that a wealthy nation has the capacity and the moral obligation to welcome them. It means admitting that we are all migrants in some sense, that we all depend on the hospitality of others, and that the stranger is not a threat but a human being deserving of dignity.

Finally, it requires a new kind of moral patience. The work of reconstruction will not be quick or easy. It will be met with fierce resistance from those who profit from the current system. It will involve us building coalitions across lines of race, class, and culture. It will require us to accept that progress is often slow and incremental. It will need us to find a way to sustain our hope and our determination in the face of setbacks and disappointments. This is the patience of persistence and understanding that change does not come through a single moment of rupture, but through the slow accumulation of small victories: the gradual shift in consciousness, the patient building of alternative institutions and alternative ways of living.

The Role of the Citizen

Where does this work begin? It begins in the daily life of the citizen. The habits of solidarity are learned and practiced in the home, in the workplace, and in the community. A nation capable of defending democracy is a nation of citizens who have learned equality in their daily lives.

Citizenship as a Practice. The most fundamental act of citizenship in a democracy is simply to show up. It is to vote, of course, but it is also to attend the public meeting, to join the local organisation, to pay attention to the news, to engage in the difficult and often frustrating work of self-government. It is to stay engaged even when (especially when) you are disappointed. The politics of spectacle is designed to exhaust us, to burn us out, to convince us that our efforts are futile. The practice of citizenship is the refusal to be exhausted. It is the quiet, stubborn, and essential work of tending to the machinery of our common life.

Refusing Dehumanisation. The politics of anti-solidarity is a politics of dehumanisation. It is a politics that invites us, and often rewards us, for seeing the other as less than human. The practice of citizenship is the refusal of this invitation. It is the conscious and deliberate effort to see the humanity in those with whom we disagree, to resist the easy and seductive pleasure of contempt, and to hold fast to the principle that every human being has a claim on our respect and our concern. This is not a matter of sentiment, but a matter of democratic survival. A society that makes a habit of dehumanising its own is a society that is preparing itself for atrocities.

Memory as Resistance. The politics of the strongman is a politics of forgetting. It is a politics that seeks to erase the past, to rewrite history, to replace the complex and often difficult story of nations with a simple and self-serving myth. The practice of citizenship is the practice of memory. It is the work of remembering how our institutions were built, and how they were lost. It is the work of teaching our children the history of the struggle for freedom and justice, not as a story of inevitable triumph, but as a story of contingency, of courage, and of choice. It is to remember that the rights we enjoy today were not given to us. They were won, by ordinary people who refused to accept the world as it was, and who dared to imagine that it could be otherwise.

Good Politics Begins at Home

This is the deeper meaning of ‘good politics begins at home.’ A home where power is not abused, where fear is not a tool of control, and where obligation extends beyond the self is a school of democracy. A workplace where workers are treated with dignity, where their voices are heard, and where they have a share in the wealth they create is a laboratory of solidarity. The way we treat our children, our partners, our colleagues, and our neighbours is the raw material of our political life. These daily interactions are not separate from politics; they are the foundation of politics. They are where we learn whether power can be trusted, whether our voices matter, whether we are equal or subordinate. They are where we learn whether solidarity is possible.

This is not to say that national politics does not matter – it matters enormously. But the capacity to build a just and humane society at the national level is forged in the crucible of our everyday interactions. A people who are accustomed to domination and submission in their private lives will not be able to sustain a democracy in their public life. A people who have learned the practice of solidarity in their families and their communities will be the last line of defence against the politics of unfreedom.

This is not a glamorous form of politics. It is the quiet, patient, and often thankless work of being a citizen. It is the work that our parents and grandparents understood when they gave up their youth to the battlefields of Europe and beyond, pushing back the darkness of fascism. But we do not need battlefields to defend democracy now. We need the same commitment, the same willingness to sacrifice comfort and convenience, and the same moral clarity about what is right. We must build institutions, defend them, demand that they serve all of us. We have to speak truth to power, organise, protest, vote, and show up. It is the work that saved democracies back then, and it is the work that will save them now.

Conclusion: The Quiet Work That Saves Democracies

The work of solidarity is the work of repair. It is the patient, difficult, and often thankless task of mending the social fabric, of rebuilding the institutions that protect us, and of restoring the trust that makes a shared life possible. This is certainly not a politics for the faint of heart but is a politics for those who have looked into the abyss and have chosen, against all evidence, to build something better. It is a politics that understands that the arc of the moral universe does not bend on its own; it must be bent, by us, through our collective effort.

This is not a politics that promises a final victory. It promises something far more valuable: a future that is not a repetition of the past. It is the agreement that we will face the future together, and that no one will be left behind. It is the conviction that our own freedom is bound up with the freedom of others, and that our own dignity is incomplete without the dignity of all. It is the choice not to abandon one another.

The work is hard. It will not be finished in our lifetime. There will be setbacks and defeats. There will be moments when the forces of division seem overwhelming, when the machinery of anti-solidarity appears unstoppable, when the temptation to give up feels almost irresistible. But this is precisely when the work matters most. This is when we must hold the line. We must remember that we are not alone, that millions of others are doing the same quiet work in their own communities, their own families, their own workplaces. We must refuse the lie that there is no alternative.

The five pillars of good politics — limits on power, fear reduction, expanded obligation, equality, and the freedom to speak truth to power — are not a blueprint for a perfect society, but they are a compass for a better one. They are a guide for those who choose to build rather than to destroy, to include rather than to exclude, to repair rather than to ruin. They are the foundation upon which a life of dignity can be built, not just for ourselves, but for all.

Politics owes us dignity, security, and the freedom to live without fear, as well as the chance to see ourselves reflected in our institutions, to know that we matter, and to believe that our voice counts. It also owes us a future in which we are not abandoned. These debts are not paid through spectacle or performance, through the crushing of enemies or the promise of greatness. They are paid through the slow, difficult work of solidarity, of building a society in which we hold one another up, in which limits bind the powerful, in which fear recedes, in which obligation expands, in which equality is not a dream but a practice.

This work is possible. It has been done before, and it can be done again. It begins with us, here, now, with the choice to refuse to abandon one another. We do this work not for ourselves alone, but for those who will come after us, to pass on to the next generation a democracy that is still worth defending, and the knowledge that solidarity is not a luxury, but a necessity, and that the work of holding one another up is the most noble work of all.

Dedicated to James and his generation, and to E, L, and G, and their generation.

Or support us with a one-off tip → Buy Me a Coffee

References

Debord, G. (1967) The Society of the Spectacle. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/debord/society.htm [Accessed: 4 January 2026].

Eley, G. (1996) ‘The End of the Welfare State? The “Crisis of the Welfare State” in Comparative Perspective’, Journal of Modern History, 68(2), pp. 417–452. [Accessed: 4 January 2026].

Fraser, N. (1995) ‘From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a “Post-Socialist” Age’, New Left Review, I/212, pp. 68–93. [Accessed: 5 January 2026].

Levy, S. (2021) Facebook: The Inside Story. Blue Rider Press.

Lorenz, C. (2005) ‘Will the Past Be a Foreign Country? The “Memory Crisis” and the Study of History’, History and Theory, 44(3), pp. 335–353. [Accessed: 5 January 2026].

McCarthy, L. (2017) To Call It a Day: The New Deal, Old Age, and the Remaking of American Life. Oxford University Press. [Accessed: 5 January 2026].

O’Neill, M. and White, S. (2018) ‘The Case for Trade Unions’, Renewal: A Journal of Labour Politics, 26(2), pp. 5–15. [Accessed: 5 January 2026].

Pew Research Center (2023) Politics and Partisanship. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/ [Accessed: 4 January 2026].

A wonderful post. The optimist in me agrees with your arguments for rebuilding and recovery. The pessimist tends to think of social systems in ecological terms where increasing instability leads to catastrophe. Some people will surely survive, but humanity may not...