Threads of Duty: My Grandfather, Fascism, and the Legacy I Refuse to Forget

The Ribbon in My Hand

It is frayed now. The stitching is loose in places, pulled and tired from years of being handled more than worn. A sliver of red, green, blue, and gold cloth, folded sharply once upon a time, stitched with care by a young man who hadn’t yet become anyone’s husband, anyone’s father, anyone’s grandad.

This is my grandfather’s hand-sewn medal ribbon.

It doesn’t look like much at first glance, just a faded strip of coloured threads, its edges a little ragged, the threads at the back curled like nerves. But when I hold it between my fingers, I feel the tremor of the life it has travelled through. He sewed it himself, I’m told. It was what soldiers often did: stitch their ribbon bars by hand, so their service could sit neatly above their heart.

Long before I existed, this ribbon sat on the chest of a young man named James, standing among others who believed they had to go. Something terrible was happening in the world, and he couldn’t stand by while it spread. He left behind a mother and sisters in a little house in the Midlands. He had no children yet, no grandchildren to imagine or protect in the abstract, only the people already in his world, and a belief that fascism was wrong.

As a child, I didn’t understand what the ribbon bar meant. I only knew it mattered. Now, when I touch it, I don’t just think of the uniformed young man in black-and-white photographs. I think of the grandfather who would one day hold my tiny hand while I ate an ice cream on a summer holiday. The man whose leg would never fully heal, whose vision would never be the same, whose sleep was often shattered by horrific memories he never spoke of in full.

This ribbon is not decoration. It is evidence: of what he endured, of what he believed in, and what he thought was worth fighting against.

The Young Man Who Went to War

Before he was my grandfather, he was just a young man from Birmingham who firmly believed that some things were worth standing against. Fascism was not an abstract ideology to him. It was a threat. A darkness spreading across Europe, pulling people into fear and brutality. When he enlisted, he wasn’t yet anyone’s husband or father. There were no children or grandchildren in his imagination, only his mother, his sisters, and he didn’t want them to suffer under tyranny.

The military records I obtained this year list his postings with clinical precision. Units. Dates. Injuries. Movements across continents marked not in emotion, but in administrative ink. But reading them, I could almost see him: boots perfectly laced, pack on his back, black hair neatly combed in the way I’d later recognise in old photographs. He didn’t yet have the softer eyes I’d know as a child - eyes shaped by time, pain, and tenderness. He was nineteen, maybe twenty. Old enough to fight. Too young to realise how long war can live inside a person.

He didn’t go to war out of naivety, and it was not reckless glory that drove him. Working-class boys like him didn’t talk about honour in lofty tones, but they understood right from wrong in a way that didn’t require philosophical training. Fascism was wrong. That’s that.

He became a signaller, responsible for communications, a role that required precision under pressure. Signalmen often stood between order and chaos, and I wonder now whether the constant vigilance, the listening for danger in bursts of static, played its role in the sleeplessness that haunted him years later.

There are no photographs of him in battle, only the afterwards, the staged portraits where he tries to look composed, like a man who’s already seen too much and is trying to fit back into his own skin. One of those photos hangs in our family collection: his jaw still smooth, uniform fitting like it was made for him, a small, incomplete ribbon bar shining above his pocket. A boy trained to stand like a man.

It is strange to think that the man who would one day hoist me onto his shoulders once walked into a war not knowing whether he would walk back out.

He fought not because he was unafraid (I have come to realise that he was actually terrified) but because he believed he should. In the quiet spaces left in his wake, I can still feel the weight of that decision.

The Cost That Never Fully Ended

The official file lists his injuries in unemotional terms: a bullet to the leg causing severe trauma and nerve damage; a serious ocular injury due to a rifle bolt backfiring. The words are clean, neat - like they belong to paperwork rather than a body. But these were not temporary wounds. They were lifelong sentences: pain that walked with him, even when the war was over and he was technically one of the ‘lucky ones’ who came home.

He nearly lost a leg. He nearly lost an eye. When I learned this, I found myself looking again at photographs of him later in life. His eyes, always slightly strained through his thick bifocal glasses, would randomly water and annoy him. The way his walk carried a subtle unevenness, a cadence interrupted by nerve damage that never healed the way medicine hoped it would. As a child, I never questioned it. I thought that was just how Grandad walked.

But war leaves marks even where nothing is torn or broken.

He was a man who carried invisible tremors. He did not have language then for post-traumatic stress disorder. Few did. Men like him were simply expected to return home, find work, raise families, keep calm and carry on. But in quieter moments, something in him was unsettled, as though parts of his mind were still waiting for sounds he hoped would never come again.

He didn’t talk very much about the war, but sometimes there were fragments; half-finished sentences, a sudden tightening of his jaw when certain things were on the news, moments when he would drift somewhere far away, his expression caught between memory and dread. He could be quiet for long stretches, and now I wonder if silence was his form of survival.

He did not glamorise what he had done. He never called it heroism - only the dead were heroes. He spoke of endurance and necessity, not pride. He knew that killing people, even in a just cause, reshapes something in the human soul.

He worked hard after the war, built a life, learned to smile again. He became a husband, then a father, then, much later, the grandfather who would teach me how to play crazy golf and sit me on his knee as he read to me. But the war lived beneath all of that, like an old injury that flared when the weather changed.

I think now about how often we talk about ‘the generation that sacrificed everything,’ as though sacrifice was a single heroic moment rather than a lifetime of aftermath. War did not end for him on the battlefield. It ended slowly, unevenly, in hospital wards, in endless sleepless nights, in the ache of a leg that had once been so close to being gone.

He survived. But he never fully returned unchanged.

Legacy in Values: NHS, Peace, and Humanity

For many men of his generation, the end of the war wasn’t just about survival; it was about rebuilding a country that made such suffering worthwhile. Victory wasn’t enough. There had to be meaning. There had to be something better born from the wreckage.

For my grandfather, part of that meaning was the birth of the National Health Service. He spoke of the NHS not as a policy or political football, but as a miracle. He lived through a time when healthcare depended not only on need, but affordability. His and my grandmother’s first child was born just before the NHS existed. I have been told it was a difficult home birth where, after the fear and the pain, there was a bill to pay. He remembered handing over money to the midwife, remembered a doctor being called out and the anxiety of knowing that every additional intervention meant more cost.

Their later children were born under the NHS - safely, in hospital, with skilled medical staff whose help did not come with an invoice or a whispered worry about debt. “It was wonderful,” he once said. “To know you could get help without keep thinking how to pay your dues.” For him, this was dignity restored, fear removed, a line drawn between the world he had fought to leave behind and the one he hoped his children would inherit.

The NHS, to him, was one of the things Britain got right - proof that a country forged in wartime solidarity could choose compassion in peacetime.

He also believed deeply that war should be avoided. He had fought fascism because he believed there was no other choice. But that experience shaped his belief that conflict must never be casual or politically convenient. When the Iraq War began decades later, he was shaken. “I don’t want to see young lads and lasses go off for nothing!” he said. “What’s it all for?”

He did not speak in slogans or wave placards, but his words left no doubt: a war without just cause was not patriotism - it was betrayal. To send another generation to fight a war rooted in lies or power games felt, to him, like spitting on the graves of those who never came home.

His values were not complicated. They were rooted in experience and sharpened by pain:

War should only be fought when it must be fought.

Healthcare should never be a privilege.

Governments should protect people, not gamble with their lives.

Sacrifice demands responsibility from the generations that follow.

These were not abstract ideals to him. They were carved into his life in scars and sleepless nights.

When the World Shifted Again: Iraq, Memory, and the Return of a Shadow

I was old enough to understand by then that my grandfather did not talk about the war often, but I also knew when something disturbed him. The Iraq War did. He watched the news sitting bolt upright in his armchair, with a kind of silent dread; a heaviness I recognised from the way he sometimes went quiet when confronted with things that echoed old fears.

For him, war was a wound. You didn’t open it unless the alternative was worse. He had fought fascism because he believed it had to be stopped. He saw Iraq as something entirely different. Something avoidable. Something careless. Something that betrayed the sacredness of sacrifice.

I did not fully grasp then how deeply he feared history repeating itself, not in the same uniforms, but in the same patterns of deception, propaganda, and dehumanisation.

But I understand it now.

I live in a time when the far right rises again, not in jackboots and marching salutes (though sometimes even that), but in dog whistles turned foghorns. In immigrants blamed for everything. In polarising ‘us’ and ‘them’ politics designed to strip human dignity from entire groups. In strongman leaders who promise order through fear. In crowds chanting about taking back a country they never lost.

And with this, I feel something inside me recoil with a deeply personal anger. What my grandfather and his generation fought for is being unraveled by people who claim to love the very country they are hollowing from within.

My grandfather lived with shadows in his mind so that fascism would never find root here again. He believed a better world could be built; one with hospitals that didn’t demand payment at the bedside, one where justice wasn’t optional.

I refuse to let the ideology he bled to stop be smuggled back into public life wearing a fresh coat of patriotism.

I can’t ask him now what he would make of this surge of hate and division. But I don’t need to, because I already know: he would not be quiet.

A Life in Four Frames

There are four photographs and objects I return to when I think about my grandfather. Each one feels like a doorway into him, in all his different forms: young, brave, wounded, loving, enduring.

1. The Ribbon - Duty Stitched by Hand

A now very old, worn strip of medal ribbon, sewn by his own hands, colours faded by time. This is the beginning of the thread. Before medals were mounted, before memories hardened into stories not often told, there was this: a young soldier quietly stitching proof of service over his heart. It is makeshift and imperfect, like real courage always is.

2. The Medals and the Hat Pin - Survival Made Tangible

In another photo, his medals lie neatly arranged beside his regimental cap badge. They gleam in a way his actual experience never did. Displayed like this, they almost look triumphant, but I know better. These are symbols of endurance, not glory. Of a war survived but not left behind. The hat pin is small, but it carries the gravity of belonging - to a moving unit, to moments in time, to a fight he did not choose, but battled through out of necessity.

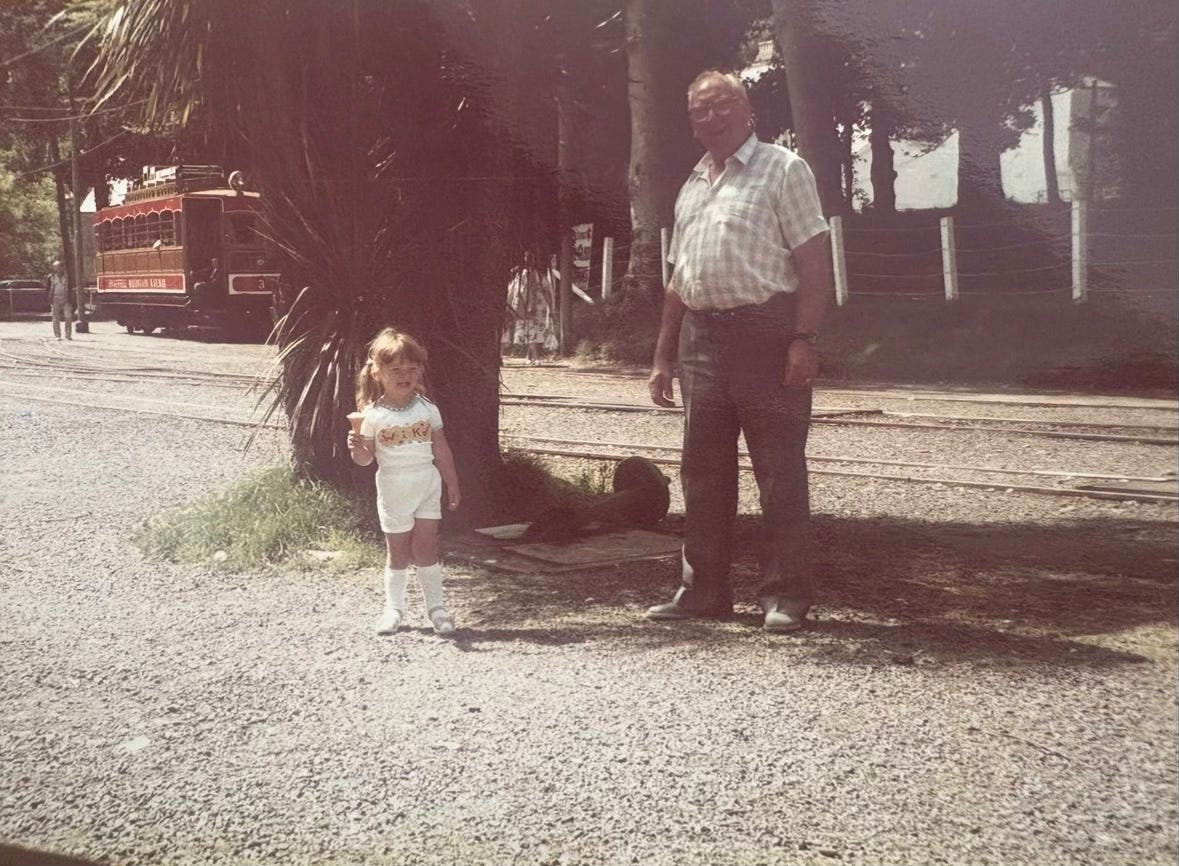

3. Me and Him - A Quiet Legacy in Motion

Then there is the photograph of us together - me impossibly small, him already older than the soldier I imagine. I do not remember the exact moment it was taken, only the feeling of his steady, comforting presence. I sometimes wonder how many times that leg - damaged long before I was born - ached as he walked at my pace, so I didn’t lag behind. To the world, he’s just a grandfather with his grandchild. To me, he is someone who endured hell and still chose gentleness.

4. The Creased Baby Photo - A Life Before War

Finally, there is the baby photograph, creased, worn at the fold, edges soft from decades of handling. He is about eight months old, cheeks rounded, hair wispy, eyes full of a softness untouched by anything harsh. I like to think my great-grandmother carried this image with her, creased not from neglect but from love - folded into handbags, pockets, perhaps clutched during long nights of worry once he went to war. Seeing him like this, just a baby, someone’s child, unravels the distance between the soldier and the man I knew. It reminds me that everyone called to war was once vulnerable, held, and loved.

These four images are not separate lives. They are one continuous thread:

The boy becomes the soldier.

The soldier becomes the survivor.

The survivor becomes the grandfather.

The legacy becomes mine.

Carrying the Thread Forward - My Responsibility Now

I think about Grandad most days. It’s not just at Remembrance time, or when war is mentioned on the news, or when far-right slogans begin to reappear in public life like an infection we once thought cured. I think of about how family-oriented he was; how kind, funny, loving, and generous he was. I think about how he’d react in moments when I see hatred being dressed up as patriotism.

I know what he fought for, and I know what he suffered because of it. He didn’t hand me a speech or doctrine when he passed away. He didn’t leave behind a manifesto or ask me to be political. He simply lived his life in a way that made it impossible for me to forget the cost of silence.

The thread that began when he stitched that ribbon has not ended; it runs through me now. It tugs at me when I see people cheered for preaching division. It pulls tighter when I hear talk of ‘others’ as though humanity can be split into worthy and unworthy. It burns when fascism creeps back in new disguises, asking us to forget what was once fought at such a price.

His generation didn’t defeat fascism so we could later flirt with it. They didn’t sacrifice so we could shrug when it resurfaces in parliaments, protests, or online echo chambers fuelled by cruelty disguised as strength.

He walked through war so others wouldn’t have to. And yet, here we are, watching history try to turn back on itself.

I cannot fight in the way he did; I hope I’ll never have to. But I can think. I can write. I can remember. I can refuse to look away. I can say, with full conviction, that the world he believed was worth fighting for is worth defending still - not with blind nationalism, but with compassion, justice, solidarity, and the refusal to dehumanise those who stand across from us.

He did not leave me with just his medals. He left me a mirror. And when I look into it now, I ask myself:

Am I holding the line? Am I allowing what he stood against to re-emerge unanswered?

The answer I want my children to inherit is this:

No. I did not stay silent.

So I carry the thread forward because it was stitched into me long before I understood its meaning.

Eloquent, beautiful!