The House Always Wins: Architecture, Power, and the Private Worlds of Autocratic Men

It began with a cloud of dust, a plume of pulverised history rising over the manicured lawns of the White House in October 2025. The sickening crunch of steel-toothed machines tearing into the elegant façade of the East Wing was a violation rather than a renovation. Where a graceful wing of neoclassical architecture had stood for over a century, there was now only a gaping wound. It was a brutal, almost gleeful, demolition (CNN, 2025).

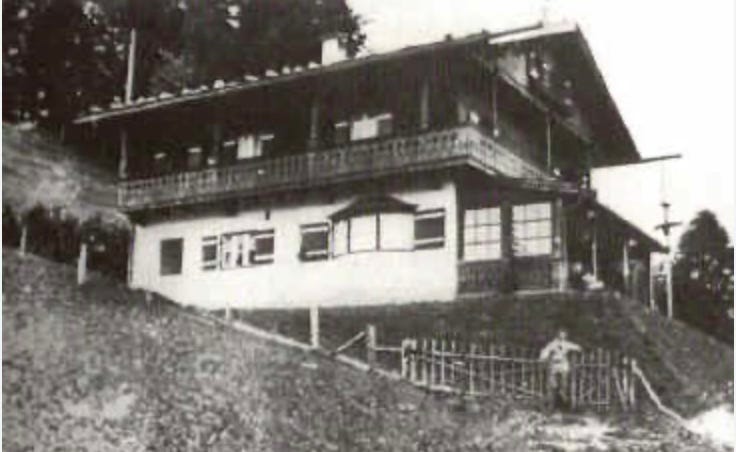

Eighty-seven years earlier, in September 1938, another leader stood on the steps of his own architectural statement. As British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain ascended the grand staircase of the Berghof, Adolf Hitler’s Alpine residence, he was walking into a meticulously crafted stage set. The house, with its panoramic views and rustic grandeur, was designed to project an image of a man at one with nature, a leader of immense but peaceable power. Chamberlain, like the world, was being played, and the architecture was a key instrument in the deception (Stratigakos, 2015).

Leaders may speak through speeches, but their most revealing messages are embedded in bricks, windows, and rooms. Architecture is political language, a physical manifestation of ideology. It is never neutral, especially when a leader reshapes the very seat of government to resemble their private world. The demolition of the White House’s East Wing to make way for a gilded ballroom in the style of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort, and Hitler’s elevation of his private mountain home into a parallel seat of government, are two sides of the same debased coin.

This essay will argue that both men, separated by time, context, and the scale of their crimes, used architecture to dissolve the boundary between personal comfort and national governance. In doing so, they revealed a core instinct of the autocratic mindset: the desire to turn public institutions into extensions of private fantasy. This is a journey through aesthetics, psychology, and the authoritarian imagination, demonstrating how the walls, windows, and rooms of power often reveal the direction of politics long before official policy does.

Architecture as Ideology: Why the Space Matters

Architecture is a form of soft propaganda. It shapes behaviour, signals hierarchy, and naturalises authority. From the imperial palaces of Rome to the monumental structures of the Soviet Union, dictators have always understood that buildings can be weapons. They use them to project permanence, inevitability, and a personal mythos that elevates the leader above the messy business of the state (Birman, 2025).

This is the concept of domestic autocracy: a political condition where the private tastes and comforts of the ruler become the template for public rule. The line between the personal and the political is more deliberately erased than merely blurred. The nation is remade in the image of the leader’s living room. This is not only an aesthetic choice. It is a profound political statement that signals a shift from institutional governance to personalist rule, a system where power is concentrated in a single individual who operates outside of established norms and laws (Svolik, 2017).

In such a regime, the leader’s personal environment becomes the true centre of power. Decisions are made not in formal offices of state, but in the insulated comfort of a private court. The architecture of these spaces is designed to reinforce the leader’s ego, to create a stage for the performance of power, and to intimidate and overwhelm visitors. It is a physical manifestation of the leader’s belief that he is the state.

Trump’s desire to impose a singular architectural vision on the American government is not merely a matter of taste. His 2025 executive order, ‘Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture,’ which mandates a classical style for federal buildings, is a top-down attempt to dictate the aesthetic identity of the nation. It is a rejection of pluralism in favour of a rigid, Eurocentric ideal of beauty and power (Birman, 2025). This is the architectural equivalent of a loyalty oath, a demand that the very buildings of the state pay homage to a singular, approved vision of history and culture.

Hitler and Trump, despite their vastly different contexts, express a remarkably similar instinct. Both men sought to create architectural environments that would serve as both a refuge from the constraints of institutional governance and a stage for the performance of their own personal power. Their buildings are not just structures of brick and mortar; they are psychological documents, autobiographies written in stone and glass.

The Berghof: Power in the Alps

Hitler’s retreat in the Bavarian Alps was more than a holiday home; it was the second seat of the Reich, a place where the informal, personality-driven nature of Nazi rule was made manifest. It was here, far from the institutional constraints of Berlin, that Hitler could perform his role as Führer on his own terms.

Hitler’s Working Style and the Turn from Berlin

Historians have long noted Hitler’s profound disinterest in the mundane realities of structured work and administrative routine. He was not a desk-bound dictator. He preferred to govern through informal conversations, monologues, and sudden pronouncements, often late at night. His daily routine at the Berghof was notoriously undisciplined; he would often wake late, around 10 a.m., and stay up until the early hours of the morning, watching films and holding court with his inner circle (CBS News, 2010). The Berghof was the perfect environment for this style of rule. It was a court, not an office, a place where personal loyalty and proximity to the Führer were more important than formal titles or institutional roles.

The Architecture of Mythmaking

The Berghof itself was a masterpiece of political stagecraft. Originally a modest chalet named Haus Wachenfeld, it was extensively remodelled in 1935-36 by the architect Paul Troost. The name ‘Berghof’ translates to ‘farmer’s court,’ a deliberate and brilliant piece of branding that combined rustic, volkisch authenticity with the aristocratic connotations of a royal court (Stratigakos, 2015).

The most famous feature of the Berghof was its Great Hall, dominated by a massive picture window revealing a breathtaking, unobstructed view of the Alps. This window was a proscenium arch, framing the landscape as a sublime and powerful backdrop for the Führer. It was a demonstration of both technological mastery and a quasi-mystical connection to the German soil. The architecture drew heavily on German Romanticism, casting Hitler as a solitary, visionary figure communing with the forces of nature (Stratigakos, 2015).

The interiors, also designed by Troost and his wife Gerdy, were a carefully curated blend of rustic simplicity and classical grandeur. The use of local woods and stone was combined with oversized furniture, valuable tapestries, and classical art to create an atmosphere of intimidating power. Paintings such as Paris Bordone’s Venus and Amor were displayed as “almost cartoonish symbols of Hitler’s hypermanliness and heterosexuality,” a deliberate attempt to counter rumours about his private life (Duggan, 2015).

Diplomacy as Theatre

The Berghof was the primary stage for Hitler’s diplomatic performances. When Neville Chamberlain arrived in 1938 to negotiate the Munich Agreement, he was deliberately subjected to a carefully choreographed architectural experience. He was first received in the overwhelming grandeur of the Great Hall, a space designed to dwarf and intimidate visitors. He was then led to a smaller, more intimate study, filled with books and art, where he encountered a seemingly “civil, cultured” Hitler, a man of taste with whom one could supposedly reason (Duggan, 2015). The architecture was an essential part of the deception, creating a false sense of security and reinforcing the myth of Hitler as a reasonable statesman.

The Politics of Comfort

It is tempting to dismiss Hitler’s preference for the Berghof as mere laziness, a desire to escape the rigours of governing. But this would be to miss the point. The retreat to the mountains was not an abdication of power, but a relocation of it to a more congenial environment. The preference for ruling from a place of personal comfort is a key feature of the autocratic mindset. Autocrats seek to surround themselves with loyalists, to create an echo chamber where their own views are reinforced and their authority is never questioned. The Berghof was the ultimate echo chamber, a place where Hitler could perform his role as Führer without the inconvenient intrusions of institutional procedure or dissenting opinions.

Mar-a-Lago Comes to Washington: Trump’s East Wing Ballroom

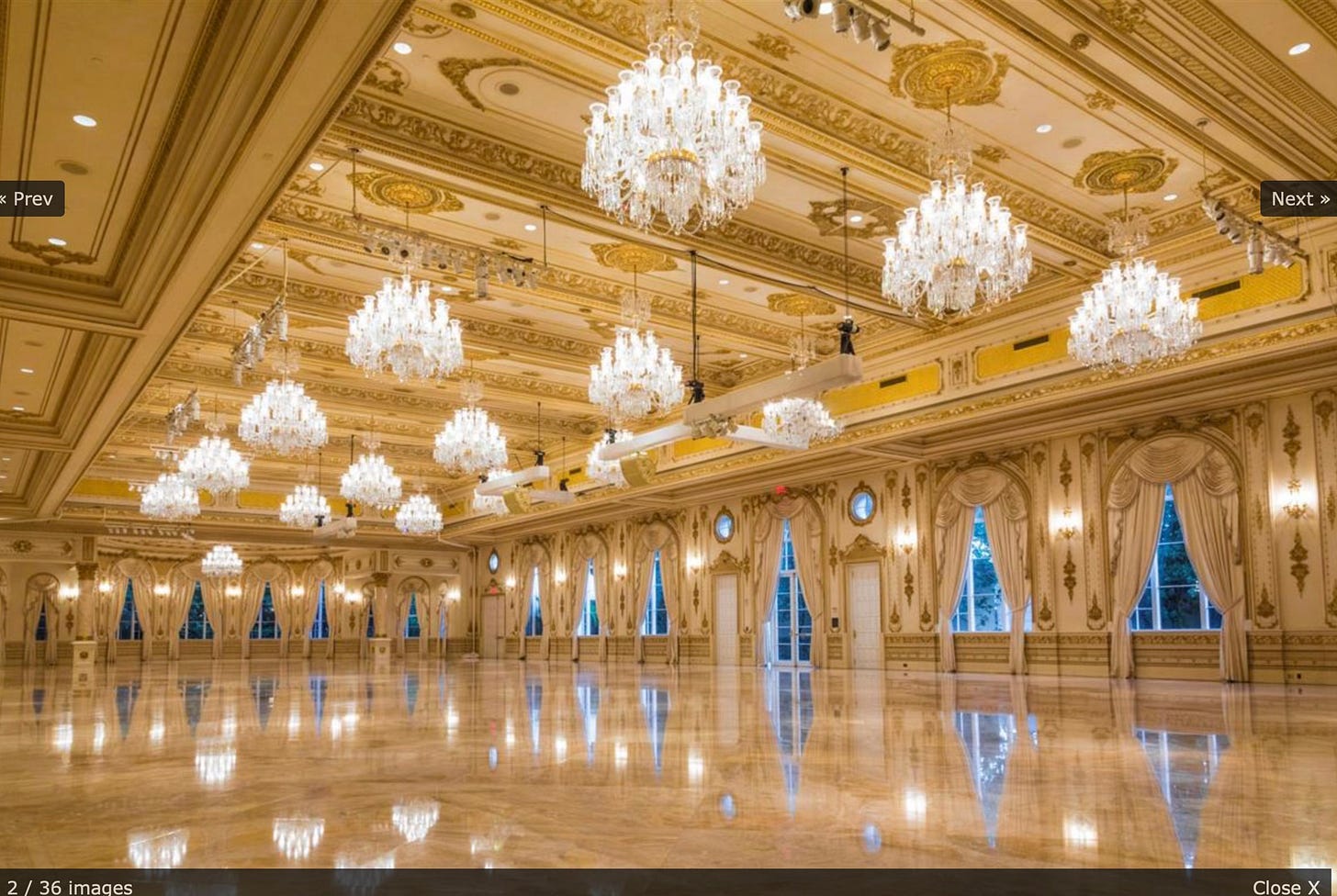

In October 2025, the wrecking balls arrived at the White House. The demolition of the East Wing, a structure that had stood for over a century, was a shocking act of architectural vandalism. In its place, a new, 90,000-square-foot ballroom is being constructed, a gilded monument to Donald Trump’s personal brand and a physical manifestation of his contempt for the traditions of American democracy.

The Symbolism of Copying Mar-a-Lago

The new ballroom is, by the White House’s own admission, designed to evoke the aesthetic of Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s private club in Palm Beach, Florida. The renderings show the same opulent chandeliers, the same neoclassical columns, the same overwhelming sense of gilded excess (The Guardian, 2025). Mar-a-Lago is Trump’s self-created palace, a place where he is surrounded by paying customers who are also his adoring fans. It is a space of total control, where his every whim is catered to and his authority is never challenged. By recreating its aesthetic inside the White House, he is collapsing the distinction between public office and private brand, transforming the seat of American democracy into a franchise of his personal business empire.

The Ballroom as Stage

The new ballroom, which will be nearly double the size of the main White House building and capable of accommodating 999 guests, is not a space for governance. It is instead a space for spectacle. Trump has long complained that the White House’s existing East Room is “too small” for his purposes (The Guardian, 2025). This reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the presidency. The White House is not a hotel or a convention centre; it is the office and residence of the head of state. The purpose of its rooms is not to accommodate massive crowds for rallies and donor events, but to serve as a backdrop for the serious business of governing.

The logic of the ballroom is monarchical, not republican. It is a space designed for a ruler to preside over a courtly gathering, to receive the adulation of his followers, and to dispense favours to his loyal subjects. It is a stage for the performance of power, not the exercise of it.

Architectural Narcissism

The gilded aesthetic of the new ballroom is a perfect expression of architectural narcissism. The mirrors, the chandeliers, the cream-and-gold tones - all of it communicates a fantasy of wealth and celebrity, not a national ethos. This is not an architecture that speaks of democratic values - of humility, service, and the common good. It is an architecture that speaks of personal enrichment, of luxury as a sign of virtue, of power as a tool for self-aggrandisement. Trump is not building for the country; he is building for the camera, for his wealthy donors, and for himself.

Replacing Democratic Symbolism

The demolition of the East Wing is a profoundly symbolic act. The wing, first built by Theodore Roosevelt and expanded by FDR, was home to the First Lady’s office and the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden. It was the public entrance to the White House, the place where tourists and guests were welcomed. It represented the ‘social side’ of the presidency, the point of intersection between the state and the people (The Guardian, 2025). Its destruction is a physical manifestation of Trump’s contempt for these softer, more inclusive aspects of governance.

Critically, the demolition was an act of autocratic defiance. After initially promising in July 2025 that no existing structures would be touched, the administration proceeded to raze the entire wing without the legally required approval from the National Capital Planning Commission (The Guardian, 2025). This is architectural rule by decree. The project is being funded not by taxpayers, but by a consortium of corporate donors, including Apple, Amazon, Meta, and Lockheed Martin. As former George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum noted, this amounts to “paying for the demolition with money from cronies and insiders seeking government favors … and the Republicans in Congress acquiescing as Trump treats public assets as private property” (The Guardian, 2025).

The Politics of Comfort

Like Hitler retreating to the Berghof, Trump is seeking to remake his environment into a space where he feels comfortable, adored, and insulated from criticism. The White House, with its historical weight and its institutional constraints, is an uncomfortable place for a man like Trump. It is a constant reminder that his power is temporary and conditional. The new ballroom is an attempt to escape those constraints, to create a space within the White House that feels more like his own private kingdom. It is the architectural equivalent of a safe space for a would-be autocrat.

The Psychology of Private Palaces: What These Choices Reveal

The architectural choices of leaders are never arbitrary. They are psychological fingerprints left in stone, revealing deep-seated beliefs about the nature of power and the relationship between the ruler and the ruled. The parallels between Hitler’s Berghof and Trump’s ballroom are not superficial; they point to a common autocratic psychology.

Autocratic Comfort: The Desire to Rule from Home

Both leaders display a common instinct: the belief that real power is exerted not from formal offices of state, but from controlled, personal environments. This is the essence of “personalist rule,” a form of dictatorship where the leader’s personal discretion and influence supersede institutional norms (Svolik, 2017). Governance becomes informal, personality-driven, and detached from the legal and bureaucratic structures of the state. The private residence becomes the true seat of power, a place where the leader can rule by whim, surrounded by a court of loyal retainers.

The Collapse of Public/Private Boundaries

When a leader’s home becomes the seat of power (as with Hitler’s Berghof), or the seat of power is remade to look like the leader’s home (as with Trump’s ballroom), the state itself becomes personalised. The distinction between the public and the private, which is essential for the functioning of a healthy democracy, is deliberately eroded. This has real-world consequences: when the state becomes an extension of the leader’s personal will, institutions lose their independence, and the rule of law is replaced by the rule of the ruler.

Aesthetic Ideology

Hitler’s Alpine romanticism and Trump’s gilded excess are both powerful ideological statements. Hitler’s aesthetic, drawing on 19th-century German Romanticism, was designed to project an image of a mystical leader in harmony with the forces of nature and the destiny of the German people (Stratigakos, 2015). Trump’s aesthetic, by contrast, is the visual language of celebrity capitalism, a celebration of wealth and luxury as the ultimate measures of success. Both, however, are rooted in ego, performance, and the creation of a personal myth.

Buildings as Autobiography

Ultimately, these buildings are autobiographical. The Berghof, with its dramatic, stage-managed views and its blend of rustic simplicity and intimidating grandeur, reveals a messianic recluse, a man who saw himself as a visionary artist-genius, above the petty concerns of ordinary mortals. Trump’s ballroom, a gaudy replica of his own private club, reveals a monarch of spectacle, a man who sees the presidency as the ultimate branding opportunity, a platform for self-enrichment and the adulation of his followers. As one analyst noted, “Architecture is slow to change but fast to signal intent” (Birman, 2025). These buildings signal a profound and dangerous intent: the transformation of the state into a personal possession.

Historical Parallels and Divergences

It is crucial to acknowledge the vast differences between these two cases. Hitler’s architectural ambitions were inextricably linked to a program of genocide, total war, and the enslavement of millions. His buildings were designed to be the stage for a thousand-year Reich built on conquest and racial purity. Trump’s architectural choices, while deeply troubling, are tied to vanity, corruption, and a relentless assault on democratic norms, not to a totalitarian machinery of mass murder.

However, to ignore the psychological parallels would be to miss the point. The patterns of personalist rule are remarkably consistent across different historical contexts. The creation of a court, the prioritisation of self-image, the use of architectural grandiosity to project power, the reliance on spectacle, and the treatment of the state as a personal possession - these are the hallmarks of the autocratic mindset, whether in 1930s Germany or 2020s America.

Architecture, in this sense, becomes a diagnostic tool. It allows us to identify leaders who see themselves not as public servants, but as absolute rulers, and to recognise the warning signs of democratic erosion long before the final collapse.

Why Architectural Ego Matters Now

When public buildings become private stages, governance itself becomes a performance. Rooms built for spectacle replace rooms built for deliberation. The quiet, often tedious, work of democracy is supplanted by the theatricality of the court. The architecture begins to express a new hierarchy, one in which the leader occupies the centre of gravity and all others are reduced to the status of audience members or supplicants.

Presidential historian Douglas Brinkley’s lament that the demolition of the East Wing was like “slashing a Rembrandt painting” is apt (The Guardian, 2025). It is an act of cultural vandalism that reveals a profound contempt for the nation’s history and its democratic traditions. The dismissive response from Trump adviser Stephen Miller, who described the East Wing as a “cheaply built add-on structure,” is equally revealing. It is a statement of profound ignorance, a refusal to see the symbolic value of a building that has been a part of the White House for over a century.

For democracies, this shift signals profound danger. Personalist leaders remake institutions in their own image long before they dismantle them outright. They begin by changing the symbols, by altering the physical environment in which power is exercised. They understand, on a gut level, that architecture is power. As one architectural analyst has written, “Buildings and monuments are declarative; their form is fixed, their symbolism predetermined by the state, and their message unambiguous” (Birman, 2025).

Conclusion: The House That Autocracy Built

We return to the image of rubble at the heart of the American republic. The demolition of the East Wing is more than just a renovation project. It is a physical manifestation of a political ideology, a clear and unambiguous statement about the nature of power in the age of Trump.

Leaders tell their truest stories through buildings. The Berghof and the new White House ballroom, separated by time and ideology, share a central premise: that the ruler’s comfort, the ruler’s ego, and the ruler’s personal brand are the centre of the political universe. They are architectural expressions of a deeply anti-democratic impulse, a desire to escape the constraints of institutional governance and to rule by personal whim.

Democracies depend on an architecture that symbolises the people, not the ruler. They depend on public spaces that are open, accessible, and contested, not private palaces that are closed, exclusive, and designed for the performance of personal power. When a leader rebuilds the house of power to suit himself, the message is clear: the house no longer belongs to the public. The walls are speaking. The question is whether we are listening.

References

Birman, S. (2025) ‘Monuments of Control: How Authoritarian Regimes Use Architecture to Shape Power’, The Science Survey, 6 July. Available at: https://thesciencesurvey.com/top-stories/2025/07/06/monuments-of-control-how-authoritarian-regimes-use-architecture-to-shape-power/ [Accessed: 20 November 2025].

CBS News (2010) ‘New Files Show Adolf Hitler’s Daily Routine’, CBS News, 29 October. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/new-files-show-adolf-hitlers-daily-routine/ [Accessed: 20 November 2025].

CNN (2025) ‘The White House’s East Wing is now demolished. Here’s what it means’, CNN, 26 October. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2025/10/26/politics/white-house-east-wing-history [Accessed: 20 November 2025].

Duggan, B. (2015) ‘How Hitler Turned Interior Design into Propaganda’, Big Think, 21 October. Available at: https://bigthink.com/culture-religion/home-front-how-hitler-turned-interior-design-into-propaganda/ [Accessed: 20 November 2025].

Stratigakos, D. (2015) Hitler at Home. Yale University Press.

Svolik, M.W. (2017) ‘The Rise of Personalist Rule’, Brookings Institution, 23 March. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-rise-of-personalist-rule/ [Accessed: 20 November 2025].

The Guardian (2025) ‘What is the White House East Wing and why has it been torn down in Trump’s renovation plans?’, The Guardian, 25 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/oct/25/what-is-the-white-house-east-wing-and-why-has-it-been-torn-down-in-trumps-renovation-plans [Accessed: 20 November 2025].