When Education Becomes Propaganda: The Federal Overreach into America’s Memory

“I think that history is the story of the past, using all the available facts, and that nostalgia is a fantasy about the past using no facts, and somewhere in between is memory, which is kind of this blend of history and a little bit of emotion…I mean, history is kind of about what you need to know…but nostalgia is what you want to hear.” Clint Smith, ‘How the Word was Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America,’ 2021.

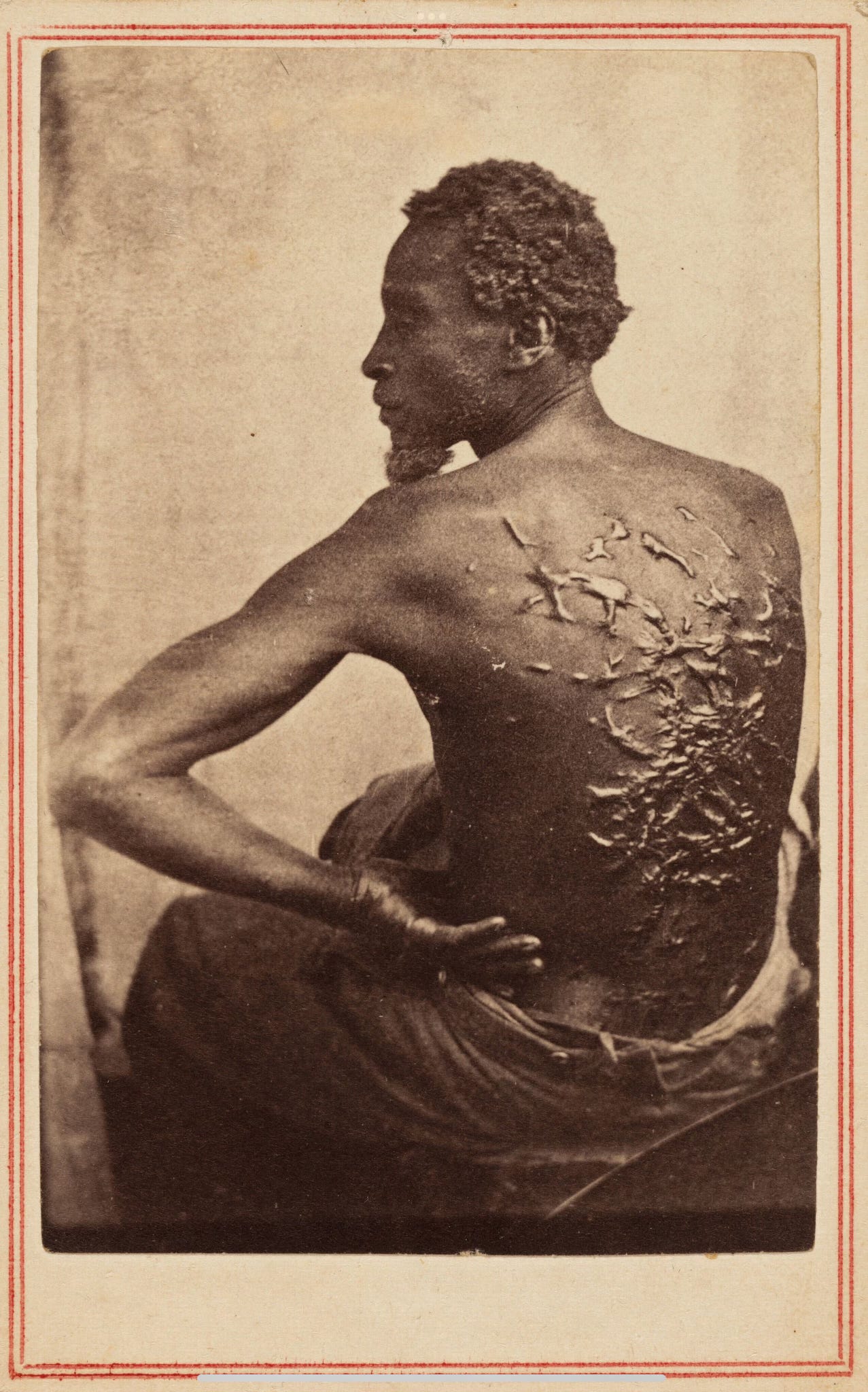

There is a famous photograph from 1863 of an enslaved man named Peter (formally known as Gordon) who escaped from slavery on a Louisiana plantation. His back, crisscrossed with scars from vicious whippings by his former overseer(s), was once printed in newspapers across the world. The image shocked nineteenth-century America into confronting what it preferred not to see. It remains unbearable to look at, but also indispensable. Today, the Trump administration has ordered the removal of signs and exhibits related to slavery at multiple national parks, including this image of Peter (The Washington Post, 2025). Without such truths, history becomes myth, and myth becomes a weapon.

History is not just a record of what has happened; it is the foundation upon which we build identity, conscience, and civic responsibility. When parts of history - especially the brutal or shameful parts like slavery, oppression, and systemic injustice - are glossed over, altered, or silenced, society loses more than facts: it loses its moral bearings. Under the Trump administration, especially since its return to power in 2025, there has been a marked push towards shaping what Americans are allowed to learn about their past. This push often seems aimed at erasing discomfort rather than confronting truth.

Take, for example, Executive Order 14190, Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling, signed on January 29, 2025. This order reestablished the 1776 Commission and mandates that federal funds not support teachings it deems “anti-American, subversive … or discriminatory equity ideology,” including concepts like critical race theory or implicit bias (The White House, 2025). The effect, or potential effect, is chilling: teachers and schools may self-censor to avoid losing funding, reducing the space for difficult, necessary conversations about America’s history of slavery and how it still shapes the present.

There is also evidence that the teaching of slavery and its legacy is already deficient in many U.S. schools. For instance, a survey by Teaching Tolerance (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2018) found that only 8% of high school seniors could correctly identify slavery as the central cause of the U.S. Civil War, and that many did not know it required a constitutional amendment to formally abolish slavery (NEA, 2018).

These developments suggest a broader trend: the suppression or sanitisation of history under the guise of preserving patriotism, protecting students from discomfort, or returning power to parents and local authorities. But who benefits when history is rewritten or hidden? And how consistent are the justifications used, especially when the same administration that argues for decentralised control of education is centralising power over what political or cultural “ideologies” may be taught?

In what follows, we argue that this overreach into historical memory and teaching methodologies is a direct threat to democratic self-understanding. While the administration frames these policies as restoring balance, defending patriotism, or protecting children, they raise serious counterarguments about free speech, academic freedom, truth, and the public’s ability to understand and challenge its own past.

What is Being Taught and What is Being Erased or Sanitised

The story of America is one of contradictions. It is a nation that speaks of liberty while built on the backs of enslaved people; it proclaims democracy while erasing Indigenous nations. The tension between myth and reality has always been present in the classroom. Today, under Trump’s second administration, that tension is being codified into policy.

The 1776 Commission, first created in 2020 and reinstated in 2025, is explicit about its mission: to centre the founding ideals of liberty and equality, while minimising the extent to which slavery or systemic racism have shaped American life (White House, 2025). Its 45-page report frames criticism of the U.S. past as dangerous “propaganda” and presents an unbroken narrative of progress. Slavery becomes a regrettable detour rather than a foundational institution; Indigenous dispossession is absorbed into a story of inevitable expansion.

This is not new. A 2018 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that most U.S. schools already avoided teaching slavery in depth: only 8% of high school seniors could identify it as the central cause of the Civil War, and textbooks often reduced it to a marginal issue (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2018). A follow-up survey by the National Education Association described the gap starkly: students were learning myths and fragments, but not the brutal truth (National Education Association, 2018). Trump’s policies risk hardening these omissions into law, turning silence into curriculum.

The administration defends this sanitisation on several grounds. Supporters argue that teaching too much about slavery, racism, or genocide risks making white students feel ashamed of their country. Others insist that such content is divisive, fostering resentment rather than unity. And a further defence appeals to patriotism: schools should cultivate pride, not guilt, in the next generation.

But these arguments collapse under scrutiny. Pride rooted in ignorance is fragile, easily shattered when the truth inevitably surfaces. Avoiding discomfort is not the same as building unity; it merely postpones reckoning. Moreover, to erase the painful chapters of history is to rob students of the very tools they need to understand contemporary America, from the racial wealth gap to mass incarceration. Sanitised history may produce more manageable citizens, but not freer ones.

The result is a narrowing of perspective. The Tulsa Race Massacre, Japanese-American internment, the genocide of Indigenous peoples - these are at risk of being omitted or recast as anomalies, rather than systemic features of American history. In this way, education becomes less about truth and more about state-sponsored memory.

Mechanisms of Control: How Overreach Works in Practice

Erasure does not happen by accident. It is engineered. The Trump administration’s education agenda is about creating mechanisms that allow the federal government to dictate the boundaries of what can and cannot be taught. These mechanisms reveal the depth of the contradiction: a government that rails against “federal overreach” in education yet simultaneously builds tools of control that reach into every classroom (The Washington Post, 2025).

Executive Orders as Directives

The clearest instrument is the executive order. In January 2025, Trump signed Executive Order 14190, which prohibits federal funds from supporting what the administration deems “radical indoctrination,” a category so broadly defined that it encompasses critical race theory, implicit bias training, and even certain diversity and inclusion programmes (The White House, 2025). The vagueness is deliberate: the more elastic the definition, the easier it is to apply selectively, silencing anything inconvenient.

The Funding Leverage

Perhaps the most powerful mechanism lies in money. By threatening to withhold federal funding, the administration turns compliance into a condition of survival. Earlier this year, civil rights and education groups filed lawsuits challenging the legality of these funding threats, warning that they amount to weaponising civil rights law to punish schools and universities that refuse to conform (American Federation of Teachers, 2025). For smaller districts already struggling with resources, the choice is stark: comply or collapse.

“Dear Colleague” Letters and Intimidation

Beyond executive orders, the Department of Education has revived the use of “Dear Colleague” letters: guidance documents sent to schools and universities. These letters warn institutions that federal funding may be withdrawn if they permit content considered “anti-American” or “divisive.” Though not formal law, such letters have enormous practical effect, producing a climate of fear and self-censorship. Administrators risk pre-emptively scrubbing curricula to avoid confrontation.

Policing Memory Through Bureaucracy

These tools may appear bureaucratic, but their cumulative impact is ideological. The message to teachers is simple: if in doubt, leave it out. Better to skip over the brutality of slavery or the violence of segregation than risk accusations of “radical indoctrination.” The chilling effect is itself the goal. History is not rewritten in a single stroke; it withers away, lesson by lesson, until silence fills the gaps.

Supporters argue this is merely restoring balance, ensuring students are not subjected to political teachings in taxpayer-funded schools. Yet this claim rests on a sleight of hand: all history teaching is political, because deciding what is included and excluded is itself a political act. To pretend otherwise is to mask ideology under the guise of neutrality.

The Contradiction: Against Central Federal Control (Except When Convenient)

One of the central mantras of American conservatism is that education should be decided locally. For decades, Republicans have condemned Washington for meddling in what is taught in the classroom, framing federal involvement as an assault on parental rights and state sovereignty. Trump himself has been no exception, railing against the Department of Education and even floating its abolition. Yet his second administration has not only preserved federal control but expanded it - so long as that control serves to enforce ideological conformity.

This is actually selective centralisation rather than decentralisation: federal power is denounced when it funds diversity initiatives, but embraced when it polices the teaching of slavery or systemic racism. The irony is glaring. The government effectively insists that Washington has no business telling schools what to teach, unless Washington happens to be telling them what not to teach.

Supporters justify this double standard by invoking parental rights. They argue that parents should be the ultimate arbiters of their children’s education, not distant bureaucrats. But in practice, these policies do not empower parents equally. They empower the loudest voices, often organised groups seeking to purge curricula of uncomfortable truths. Parents who want their children to learn the full history, including its brutal chapters, find themselves with less say.

Others defend federal intervention on the grounds of national cohesion. In a time of polarisation, they argue, the nation cannot afford to have ‘fragmented’, or ‘partisan’ histories taught across different states. Yet this very argument undercuts decades of rhetoric about localism. If unity is suddenly the priority, then federal enforcement is not only permissible but necessary. The problem is that the unity on offer is coerced, achieved through silence rather than dialogue.

The contradiction matters because it exposes intent. This is about power: who has the authority to define the nation’s memory. A truly decentralised system would tolerate difference - one district teaching the 1619 Project, another leaning on the 1776 Commission. What we see instead is an attempt to create a federally enforced orthodoxy, where only one version of America is legitimate.

When history is treated this way, democracy itself is at risk. A people denied their past cannot fully grasp their present. Citizens stripped of the knowledge of oppression are less likely to recognise it in their own time. We could identify the contradiction between rhetoric and practice not as an accident, but a strategy.

Consequences

The consequences of sanitising history are real. When students are denied the full story of slavery, segregation, or Indigenous dispossession, they inherit not knowledge, but amnesia. They become citizens less equipped to recognise injustice in the present because they have not been taught how it operated in the past.

For students, the cost is intellectual impoverishment. Already, American students struggle with historical literacy: In 2022, the average U.S. history score for eighth-grade students fell by 5 points compared to 2018, and by 9 points compared with 2014, according to the NAEP highlighted report by NCES.

Stripping away yet more content about race, slavery, and oppression risks leaving a generation unable to connect past and present. Supporters argue this will spare students from guilt or shame. Yet, discomfort is not the enemy of education; it is its engine. Learning requires grappling with complexity, not avoiding it.

For society, the cost is division disguised as unity. By presenting a sanitised, triumphalist version of history, the state deepens polarisation. Communities that see their histories erased - whether Black, Indigenous, or immigrant - are reminded again that their suffering does not count. At the same time, students raised on a diet of myth and omission may struggle to understand why others insist on remembering. What looks like unity in the short term becomes estrangement in the long term.

For democracy, the cost is profound. Democracies rely on informed citizens who can scrutinise power, weigh competing narratives, and hold leaders accountable. A people shielded from their own history are easier to govern, but harder to free. The less citizens know, the less they question.

Supporters counter that national strength depends on confidence, not criticism. They contend that too much focus on slavery or racism risks weakening patriotism and undermining military or civic cohesion. Yet this argument misreads patriotism itself. True love of country is not blind devotion; it is a commitment to make the nation better by confronting its failings. Pride built on silence is brittle. Only pride tempered by truth can endure.

In this sense, the consequences are cumulative. Intellectual narrowing produces social estrangement; estrangement weakens democracy. A nation that cannot tell the truth about itself cannot be trusted to defend the truth for others.

What We Can Do and What Should be Done

If history is the battleground, then resistance must begin with memory. The attempt to erode American education is not inevitable; it can be challenged, in the home, legally, politically, and culturally. The question is whether enough people recognise the urgency.

Legal Resistance

Courts remain one avenue. Already, educators’ unions and civil rights groups have filed lawsuits against the Trump administration’s use of funding threats to control curricula, arguing that they amount to unconstitutional overreach (American Federation of Teachers, 2025). These cases matter not only for teachers’ rights but for the principle that education cannot be reduced to government propaganda. Supporting such challenges - through legal defence funds, public advocacy, or testimony - is essential.

Defending Teachers and Academic Freedom

Teachers are on the front lines. When a “Dear Colleague” letter arrives on a superintendent’s desk, the pressure to self-censor trickles down the chain of command. Teachers need not only legal protections but also solidarity from parents and communities willing to defend their right to teach honestly. Professional organisations, like the American Historical Association, have already warned that banning “divisive concepts” undermines civic literacy (American Historical Association, 2021). Amplifying these voices, and refusing to let teachers be scapegoated, is crucial.

Alternative Curricula and Cultural Work

Silence in the classroom can be countered by noise elsewhere. Projects like the 1619 Project (Hannah-Jones, 2019) or the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Hard History curriculum (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2018) offer resources that families, local libraries, and community groups can use. If the state seeks to narrow memory, communities can widen it. In a digital era, history does not live only in textbooks because it circulates through podcasts, documentaries, and cultural work.

Public Awareness and Political Pressure

These policies thrive on distraction. When the administration pushes “patriotic education,” it cloaks censorship in the language of freedom. Exposing this contradiction repeatedly, and insisting on its dangers, is itself a form of resistance. Citizens can pressure local school boards, state legislators, and members of Congress to refuse complicity. Parents who value full history teaching must be as loud as those demanding its erasure.

The Deeper Responsibility

Ultimately, the defence of history is not only a fight for the classroom but a fight for democracy itself. It requires recognising that the stories of slavery, dispossession, and oppression are not inconveniences but truths upon which justice depends. A nation that cannot face its past cannot repair its future. To act is to insist that memory belongs to the people, not to the state.

Conclusion: Remembering for a Just Future

When we return to Peter’s scarred back at the end of this article, it is no longer only an image of pain. It becomes a mirror. His scars are reminders of what happens when cruelty is hidden, when brutality is normalised, when silence is allowed to reign. They confront us with a simple truth: history that is not told honestly will always reappear, written on the body, carried by the oppressed, carried into the future.

The danger of Trump’s “patriotic education” project is not only that it erases Peter, but that it erases the capacity of students to see themselves in him. To deny young people the knowledge of slavery, segregation, and genocide is to deny them empathy. It is to replace humanity with myth. While myths can bind a nation together for a time, they cannot give it the resilience or dignity it needs to endure.

There is a cruelty in erasure that goes beyond the facts omitted. It tells descendants of the enslaved that their suffering is an inconvenience, best forgotten. It tells survivors of racism and violence that their pain is irrelevant to the national story. It tells students that the only acceptable version of America is one where the oppressed are silent and the powerful are never questioned. Such lessons are not neutral; they are indoctrination in obedience.

And yet, the photograph of Peter survived. It was published, shared, remembered. Despite every attempt at erasure, his scars made it impossible to pretend that slavery was benign or incidental. That survival should give us hope. The state may try to narrow memory, but memory has a way of resisting. Teachers smuggle truth into classrooms. Families pass down stories. Communities mark anniversaries of massacres once scrubbed from textbooks. History leaks through the cracks, refusing to be silenced.

We have a moral responsibility. To protect memory is to protect the dignity of those who lived, suffered, and resisted. To erase it is to collude in their silencing. Democracy cannot survive that kind of collusion.

The fight over what America teaches its children is not a side issue: it is the frontline of freedom. To remember Peter is to remember that truth, however painful, is what makes us human. To forget him is to forget ourselves.

If you value this kind of writing, please consider subscribing to Plague Island.

We don’t hide our work behind a paywall, because we want it to be read. But if you can support it, we’ll use that support to keep writing more, and writing better.

Paid subscribers receive early access, behind-the-scenes newsletters, and the chance to shape future essays.

We write with rigour, we cite everything, and we answer only to our readers.

Or support us with a one-off tip → Buy Me a Coffee

References

American Federation of Teachers (AFT) (2025) ‘Educators Sue to Challenge Trump Administration’s Efforts to Weaponize Civil Rights Laws.’ 30 January. Available at: https://www.aft.org/press-release/educators-sue-challenge-trump-administrations-efforts-weaponize-civil-rights-laws [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

American Historical Association (2021) ‘Historians Respond to “Divisive Concepts” Legislation.’ Available at: https://www.historians.org/news-and-advocacy/statements-and-resolutions-of-support-and-protest/historians-respond-to-divisive-concepts-legislation [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

Hannah-Jones, N. (2019) ‘The 1619 Project.’ The New York Times Magazine, 14 August. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2023) ‘2022 NAEP U.S. History Assessment: Highlighted Results at Grade 8. U.S. Department of Education.’ Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/use-work/resource-library/report/statistical-analysis-report/2022-naep-u-s-history-assessment-highlighted-results-grade-8-nation [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

National Education Association (NEA) (2018) ‘U.S. Students’ Disturbing Lack of Knowledge About Slavery.’ Available at: https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/us-students-disturbing-lack-knowledge-about-slavery [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

Smith, C. (2021) How the Word Was Passed: A Reckoning with the History os Slavery Across America. Dialogue Books.

Smithsonian Institution (Online) ‘Peter, formally identified as “Gordon”’ Available at: https://npg.si.edu/learn/classroom-resource/gordon-lifedates-unknown [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

Southern Poverty Law Center (2018) ‘Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.’ Montgomery, AL: SPLC. Available at: https://www.splcenter.org/20180131/teaching-hard-history-american-slavery [Accessed: 19 September 2025].

The Washington Post (2025) ‘National park to remove photo of enslaved man’s scars,’ 15 September. Available at: https://apple.news/A4VBVqkkjQCaRnwLd8ONmBA [Accessed 19 September 2025].

The White House (2025) ‘Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling.’ Executive Order 14190, 29 January. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-radical-indoctrination-in-k-12-schooling/ [Accessed: 19 September 2025].