The Pendulum Will Swing Back: Why Hate Can’t Hold Forever

We’re living through an age of cruelty.

It hums through the headlines and howls across social media. Every day seems to bring a new act of division, another group told they don’t belong, another public figure rewarded for cruelty, another policy built on spite. The far right no longer hides behind euphemism; it has stepped into daylight, reshaping what counts as ‘normal’ in public life.

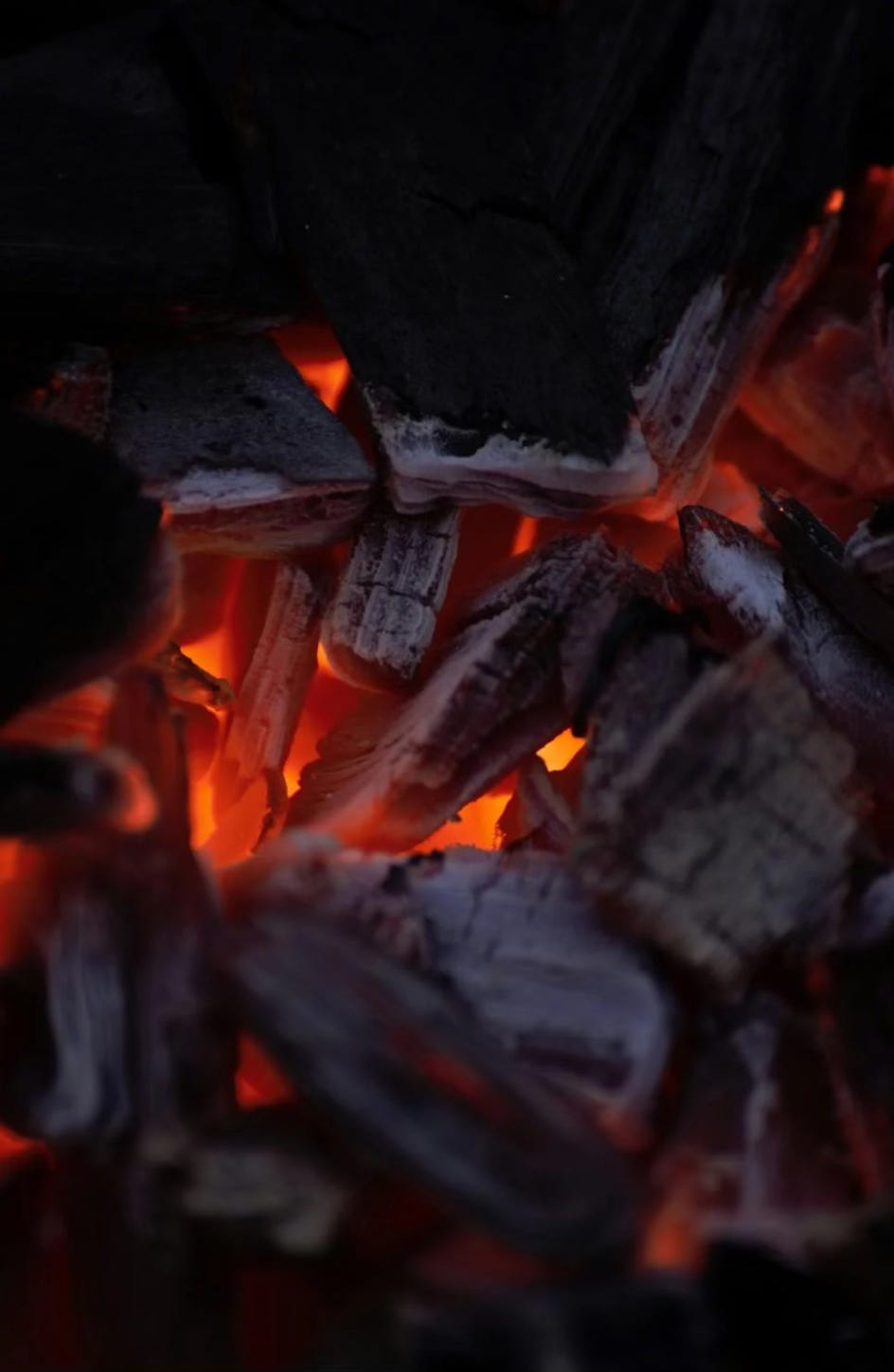

But history teaches us something comforting, even now: hate burns itself out. Like any fire, it consumes the air that keeps it alive. And when it’s finally starved of oxygen - when the rage, the lies, the fear start to feel hollow even to their believers - something new can grow in the ashes.

Once, far-right ideas were easy to spot. They marched under banners, shouted from fringes. Today they wear suits, sit in parliaments, and write columns for respectable papers. Researchers who track the spread of far-right language in mainstream politics have shown how steadily the boundaries have shifted. A study by Brown, Mondon and Winter (2023) describes how ideas that once existed on the edges - hostility toward migrants, contempt for equality, nostalgic nationalism - are now voiced by major parties and debated as if they were legitimate policy questions.

The media has played its part too. Studies of European news coverage (Cammaerts, 2018; Völker & Saldivia Gonzatti, 2024) show how journalists, desperate for controversy, have amplified the rhetoric of exclusion. Even when they claim to condemn it, they give it oxygen. The result is what academics call ‘discursive normalisation’ - what once sounded shocking now sounds routine.

And then there’s the machine itself: the digital architecture we live inside. Platforms like X (formerly Twitter) don’t reward thoughtfulness or compassion; they reward heat. A large 2021 study by researchers at Twitter found that right-leaning political content was boosted more by the algorithm than left-leaning content in six out of seven countries studied (Huszár et al., 2021). Not because the engineers set out to promote the right, but because outrage simply performs better. It’s more clickable. It keeps people scrolling.

Other researchers have since confirmed this bias (Ye, Luceri & Ferrara, 2024; Milli et al., 2023): posts that trigger anger, fear, or disgust travel faster and further than those that ask people to think. In the attention economy, cruelty is currency.

The Soil in Which Hate Grows

The digital sphere is only one piece of the puzzle. Beneath it lies something older: the ache of lives that feel smaller, harder, or forgotten. Economic insecurity, inequality, loneliness, and collapsing trust in public institutions all create perfect conditions for grievance politics. When people feel humiliated or unseen, they will listen to anyone who promises to make them matter again, even if that promise is built on scapegoating someone else.

The far right has learned how to weaponise that pain. It packages despair as identity, grievance as belonging. It doesn’t solve misery but sells it back to you with a flag and a slogan.

Outrage has become the ruling emotion of our time. It fills the airwaves and timelines, turning politics into theatre and cruelty into spectacle. But no movement can survive on rage alone. It’s too exhausting to sustain. Every authoritarian wave eventually reaches a point of burnout. The contradictions start to show: corruption, hypocrisy, infighting. People tire of being angry all the time. The slogans stop working. The strongmen start to look small. And out of that fatigue - that emotional emptiness - something quieter begins to stir.

Compassion. Curiosity. The simple, radical idea that other people are human too.

That’s where this story begins to turn, and where the next generation, the one that follows this far-right fever, will take its first breath.

The Pendulum Always Swings

History doesn’t move in straight lines. It swings. From progress to reaction, compassion to cruelty, democracy to repression, and back again. Every political order carries within it the energy of its own undoing. Push too far in one direction and something - or someone - pushes back.

We have been here before. The rise of fascism in the 1930s was followed by the social democracies of the post-war years. The authoritarian certainties of the Cold War gave way to the freedom movements of the 1960s. The neoliberal revolution of the 1980s - all markets, greed, and deregulation - spawned a generation that sought meaning in cooperation, art, and identity.

The pendulum is more than a metaphor; it’s an observable rhythm of exhaustion and renewal. The political scientist Ronald Inglehart described this in his “post-materialist shift” theory: when people grow up in times of security, they tend to value expression, equality, and quality of life over authority and survival (Inglehart, 2018). And when those freedoms are crushed, a new generation eventually rises to reclaim them.

That’s about where we are as of now, at the farthest reach of the swing.

Each wave of extremism plants the seeds of its successor. The cruelty of this moment - the nativism, the authoritarian swagger, the punitive politics of fear - will not last forever, because it runs counter to human nature’s longer moral arc.

Political scientists like Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart (2019) describe today’s far-right surge as a cultural backlash: a revolt by older, more traditional groups against decades of social progress on gender, sexuality, and race. It’s reactionary by definition: a desperate attempt to claw back control in the face of change.

But backlash is not permanence; it is the dying breath of dominance. The same data that reveal the rise of authoritarian populism also reveal its limits. Surveys across Western democracies show that younger generations - Gen Z and millennials - are consistently more progressive on equality, diversity, and climate than any generation before them (Pew Research Center, 2023). They are, statistically, less racist, less homophobic, and less tolerant of authoritarianism.

The backlash, in other words, is finite. Its power lies in noise, not numbers.

History’s Rhythms

After the Great Depression and the rise of fascism, the pendulum swung toward solidarity: the Beveridge Report, Roosevelt’s New Deal, the birth of the NHS, and the welfare states of post-war Europe. After McCarthyism and nuclear paranoia, came the counterculture - the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, environmentalism.

Even neoliberalism’s dominance since the 1980s has generated its own opposition: Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, movements that reassert the moral and collective dimension capitalism sought to erase.

Political historians often call this counter-cyclical change. When institutions drift too far from public morality, social movements drag them back. The political theorist Albert O. Hirschman saw this as a constant dance between “exit” and “voice,” people either withdraw from failing systems or speak out to reform them (Hirschman, 1970). Most do both in time.

Right now, the pendulum is still arcing outward - toward cruelty and control - but it’s slowing. You can feel it in the fatigue, in the apathy of citizens who’ve realised that rage doesn’t fix potholes or feed families. You can see it in the quiet acts of defiance: teachers, doctors, and journalists who refuse to comply with cruelty. You can sense it in art, film, and youth culture, where irony is giving way to sincerity again.

And in the data:

In the U.S. and UK, polling shows that young voters are turning sharply against the far right.

Worldwide support for Palestinian solidarity.

In Poland and Brazil, authoritarian incumbents have been ousted not by revolution, but by electorates who’ve had enough.

We are standing at the crest of the swing, watching gravity gather.

Every act of cruelty generates its opposite. The pendulum does not correct the past, but it creates the space to envision alternatives and something new to grow. What follows this age of rage will not look like the 1960s redux; it will be more intersectional, more digitally native, more global in scope.

The next wave - the one already forming in classrooms, online communities, and protest movements - will value compassion as rebellion. Its power will not be in domination but in repair.

The far right’s rise has been the great unmasking. It has shown us what happens when cruelty is systematised and empathy mocked. But it has also forced a generation to remember what it means to care. The swing will come, not because of fate or optimism, but because hate is too heavy to carry forever.

The New Age of Aquarius

Every age of cruelty gives birth to its opposite. When the world grows too cold, the next generation learns warmth. When division becomes doctrine, empathy becomes rebellion.

It’s tempting to think the pendulum simply swings back to where it started, but history rarely repeats that neatly. What comes next doesn’t look like a return to the past; it is instead an evolution born from the wreckage of what failed.

We can already glimpse its outlines. A generation shaped by climate collapse, pandemic, economic precarity, and online cruelty is developing a politics of care. They’ve seen where greed and spite lead. They’ve watched adults lie with confidence and destroy with conviction. They know the language of power by its aftertaste; the disillusionment it leaves behind.

Generational psychology often shifts when societies hit emotional rock bottom. Ronald Inglehart’s research into post-materialism found that when survival is no longer the only concern, younger generations begin to value self-expression, equality, and belonging (Inglehart, 2018). That shift is happening again, not because the young feel secure, but because they know security is an illusion.

They have grown up amid economic, ecological, and moral crises. They are rejecting the idea that cynicism is sophistication, and forming what sociologists call a values inversion: a pivot from competition to cooperation (Twenge, 2023).

Even amid despair, these are the first signs of a new collective ethic: an instinct to rebuild meaning from the ruins.

Every transformative generation develops its own mythology. In the 1960s, it was the Age of Aquarius - peace, love, community. Naïve in parts, yes, but sincere in its yearning to transcend materialism and violence. The spirit of that age is stirring again, but this time it’s tempered by the knowledge of limits.

This new wave will not seek utopia through psychedelia or communes, but through small acts of restoration, such as mutual aid networks, climate activism, digital cooperatives, and community repair. As the writer and activist adrienne maree brown puts it, “the small is all” - change begins at the most local, relational level (brown, 2017).

They will be the healers, artists, coders, and carers who reject the logic of cruelty through attention. They will embody the quiet revolution of dignity, hope, and people refusing to look away.

Signs of the Coming Shift

You can already see it, if you know where to look.

The explosion of mutual aid groups during the pandemic, which according to The Guardian (2021) involved over four million Britons volunteering to support neighbours and strangers.

The rise of global youth-led movements like Fridays for Future and the Sunrise Movement, pushing governments on climate action.

Digital creators building inclusive spaces around neurodiversity, body autonomy, and mental health - countercultures of empathy within algorithmic chaos.

History’s most compassionate generations are often born after its cruelest ones. When the noise of hate becomes unbearable, people begin to crave harmony again, as a way of survival.

Subscribe to Notes From Plague Island and join our growing community of readers and thinkers.

The Return of Meaning

We’ve spent years watching language corrode - words like ‘freedom,’ ‘truth,’ ‘patriotism’ twisted into weapons. We want the next generation to reclaim them. They’ll speak softly where their predecessors shouted. They’ll find beauty where others found dominance. They’ll seek meaning not in empire, but in empathy.

When the darkness gets too deep, humanity turns toward the light. The new age won’t arrive with a song or a slogan; it will arrive quietly, in acts of restoration: a teacher defending inclusion, a neighbour sharing food, a young person choosing dignity over cruelty. And one day, when the old order has spent itself dry, those small gestures will have remade the world.

For all the talk of apathy, younger generations are more politically awake, and more morally consistent, than any in decades.

Pew Research (2023) found that majorities of Gen Z and younger millennials support diversity, climate action, and government responsibility for equality.

In the UK, YouGov polling shows young voters increasingly rejecting the far right, with over 70 % of 18–24-year-olds believing immigration benefits the country (YouGov, 2024).

In Germany, a similar pattern is visible: as the AfD grows louder, its support among under-30s stagnates.

They are digital natives of hypocrisy: raised on performative politics, they have developed a fine-tuned radar for it. Their rebellion is sincerity.

Writers like Jean Twenge (2023) note that this generation, despite anxiety and screen fatigue, shows unprecedented empathy for mental-health struggles, neurodiversity, and social inclusion. They are less cynical, less tribal, more emotionally literate. They’ve watched the world burn and still believe it can be rebuilt.

Resistance no longer looks like it did in the twentieth century.

It’s quieter, unfamiliar, more creative, but no less radical. From the climate protests of Fridays for Future to trans writers reclaiming public narratives, and musicians using TikTok to challenge misogyny and war, rebellion has taken on new forms.

For all its noise, digital culture has also become a space for new commons - decentralised, collaborative, often anonymous communities driven not by profit but by mutual curiosity. Open-source programmers, citizen scientists, collective archives, and even meme networks have become the digital heirs of the radical pamphlet. These are fragile, hopeful, and profoundly human prototypes.

The Pendulum in Motion

The far-right moment looks powerful because it shouts. But power built on cruelty is brittle. You can already hear it cracking. In the gaps between crises, something else is growing: a politics of repair. Not a return to the arguably naïve optimism of the past, but a deliberate choice to care, to build again, knowing what broke us.

That’s how renewal begins: not with an explosion, but with a murmur that spreads until it becomes the new common sense. The pendulum is going to swing back, and the sound it will make will be the hum of ordinary people choosing decency over despair.

The last great act of defiance in a broken world is kindness. It shouldn’t have to be revolutionary to care about other people, but in an age that rewards cruelty, it is. Compassion has become subversive. To stay gentle in a culture of aggression, to refuse cynicism when cynicism is the social currency, is to stand against the current.

This is what makes healing political, because it’s about reclaiming humanity from systems that treat it as weakness. The act of repairing - bodies, communities, ecosystems - is itself a form of resistance.

Political theorists have long argued that societies rise or fall on how they value care. In The Care Manifesto (Chatzidakis et al., 2020), the authors describe care as “the connective tissue of life” - something markets cannot quantify and governments too often ignore. They call for a “care revolution,” one that places empathy and mutual responsibility at the centre of economic and political life.

It’s a radical idea precisely because it is so ordinary. It demands that we see policy as a relationship; that we judge success not by GDP but by well-being, connection, and trust. This re-centring of care is already visible: in the rise of trauma-informed education, community-based mental health networks, climate movements that link ecological repair with social justice. They’re small shifts, but collectively they represent a profound re-moralisation of public life, an insistence that how we live matters as much as what we achieve.

When the old systems finally collapse under the weight of their own cruelty, the people who will rebuild them are not the loudest, but the kindest.

Healing is not a retreat from politics; it’s the politics of the future. It asks us to confront the damage done with wisdom. That is the pendulum’s true return - not just the swing away from hate, but the rediscovery of what it means to be human.

Conclusion: The Long Dawn

History never changes overnight. The morning after collapse always looks the same: half-light, confusion, the sound of ordinary people sweeping up the glass. Renewal is never cinematic. It’s slow, imperfect, and quietly heroic.

But it comes.

The far right will not vanish with a single election or exposure. The poisons it has released - fear, cynicism, division - will linger. The damage to institutions, trust, and truth will take years to mend. Yet the same is true of every age that has stumbled toward the light.

Democracy survived fascism once. Civil rights survived segregation. Empathy has outlived every system that tried to crush it. Progress is not a straight line - it’s a long, stubborn insistence that people deserve better.

The next era will not be easy.

The climate crisis will deepen. Inequality will test the patience of democracies already stretched thin. But history suggests that exhaustion itself can be transformative. When cruelty becomes untenable, pragmatism takes its place.

Even now, governments are being forced, often by the young, to reckon with new moral economies: decarbonisation, social care, fairness. Ideas that once sounded idealistic, like universal basic income, reparative justice, and degrowth are slowly entering mainstream debate.

This is what the early hours of change look like: hesitant, uneven, but real. The pendulum doesn’t swing cleanly; it drags debris. But it moves.

The next chapter will not be written by messiahs or strongmen, but by the quiet architects of repair - the teachers, medics, engineers, and organisers who believe that decency is not naïve but necessary. Their work might not make headlines, but it will happen in policy drafts, community meetings, local repair shops, slow diplomacy, and the daily ethics of respectability. They are the ones who will turn the abstract idea of compassion into infrastructure.

Hatred is a reaction, not a foundation. It binds through fear, not loyalty. It burns bright, but it burns out, feeding on the very people it claims to protect. You can build a movement on resentment, but not a future.

Compassion, by contrast, renews itself. It’s slower, quieter, harder to monetise, but it endures. Every act of kindness plants a root where rage once took hold. Every time someone refuses to hate back, the architecture of cruelty weakens a little more.

That is why hate can’t hold forever: because it creates nothing that can outlive it.

The pendulum is already turning, not in parliaments or headlines, but in hearts; in the gentle defiance of those who still believe decency matters. History bends not toward the loudest, but toward the most steadfast: the ones who rebuild when no one is watching.

When the last sparks of anger burn themselves out, what lingers will not be ashes, but embers -

the low, steady glow of care,

enough to warm the hands of those who stayed,

and to light the way for those still coming home.

Or support us with a one-off tip → Buy Me a Coffee

References:

brown, a. m. (adrienne maree brown). (2017) Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press.

Brown, K., Mondon, A. & Winter, A. (2023) ‘The far right, the mainstream and mainstreaming: towards a heuristic framework’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 28(2), pp. 162–179. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13569317.2021.1949829 [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Cammaerts, B. (2018) ‘The mainstreaming of extreme right-wing populism in the media: discursive boundary shifts and normalisation.’ London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE Media and Communications). Available at: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/87639/ [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Dunford, J. & Updegrove, D. (2024) ‘The Pendulum Swings: Cultural Backlash and Rhythms of Democracy,’ Current,November 2024. Available at: https://current.org/ [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Hirschman, A.O. (1970) Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Huszár, F., Ktena, S. I., O’Brien, C., Belli, L., Schlaikjer, A. & Hardt, M. (2021) ‘Algorithmic Amplification of Politics on Twitter’, arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.11010.Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.11010 [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Inglehart, R. (2018) Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milli, S., Ho, A., Seetharaman, P., Xu, J., Zhang, Z., Yu, R., Horne, B. & Chen, H. (2023) ‘Beyond Engagement: Measuring and Auditing the Effects of Algorithmic Amplification’, arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16941. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.16941 [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Mondon, A. & Winter, A. (2020) Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream.London: Verso Books.

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. (2019) Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pew Research Center. (2023) ‘Generation Z and Millennial Attitudes toward Democracy, Diversity, and Climate.’ Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org (Accessed 10 October 2025).

Rothman, L. (2016) ‘History Doesn’t Move in a Straight Line - It Swings Like a Pendulum,’ Time Magazine, 14 November 2016. Available at: https://time.com/4571218/history-pendulum-donald-trump/ [Accessed 10 October 2025].

The Guardian. (2021) ‘How Covid Mutual Aid Groups Created a New Kind of Community Spirit.’ The Guardian, 7 April 2021. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/apr/07/how-covid-mutual-aid-groups-created-a-new-kind-of-community-spirit [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Twenge, J. M. (2023) Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents - and What They Mean for America’s Future. New York: Atria Books.

Völker, T. & Saldivia Gonzatti, A. (2024) ‘Discourse Networks of the Far Right: How Far-Right Actors Become Mainstream in Public Debates’, Political Communication, 41(5), pp. 579–603. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10584609.2024.2308601 [Accessed 10 October 2025].

Ye, Z., Luceri, L. & Ferrara, E. (2024) ‘Quantifying Political Bias in Twitter’s Recommendation System’, arXiv preprintarXiv:2411.01852. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.01852 [Accessed 10 October 2025].

YouGov. (2024) ‘Young Voters and Immigration Attitudes in Britain.’ Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics[Accessed 10 October 2025].