Part 11 - Carl Schmitt: How a Nazi Theorist Became the Prophet of Modern Authoritarianism

This essay is part of our ongoing series, The Dark Enlightenment: The Gospel According to Power - an investigation into how faith, technology, and ideology merge to justify authoritarian power.

The Ghost of Weimar: Schmitt’s Birthplace in Chaos

Imagine Berlin in 1932. The Weimar Republic, Germany’s first experiment with democracy, is disintegrating before the eyes of its citizens. Its parliament is fractured beyond repair, its people are polarised into warring camps, and the streets have become battlegrounds for political factions that see each other not as opponents but as mortal enemies. Unemployment is rampant, political violence is routine, and the institutions of liberal democracy appear paralysed, unable to respond to the cascading crises. Out of this chaos, a longing for order arises; a desperate hunger for someone, anyone, who can make the trains run on time and restore a sense of national purpose. And with it comes the intellectual justification for a new kind of power, one that would dispense with the niceties of parliamentary procedure and embrace the logic of emergency rule.

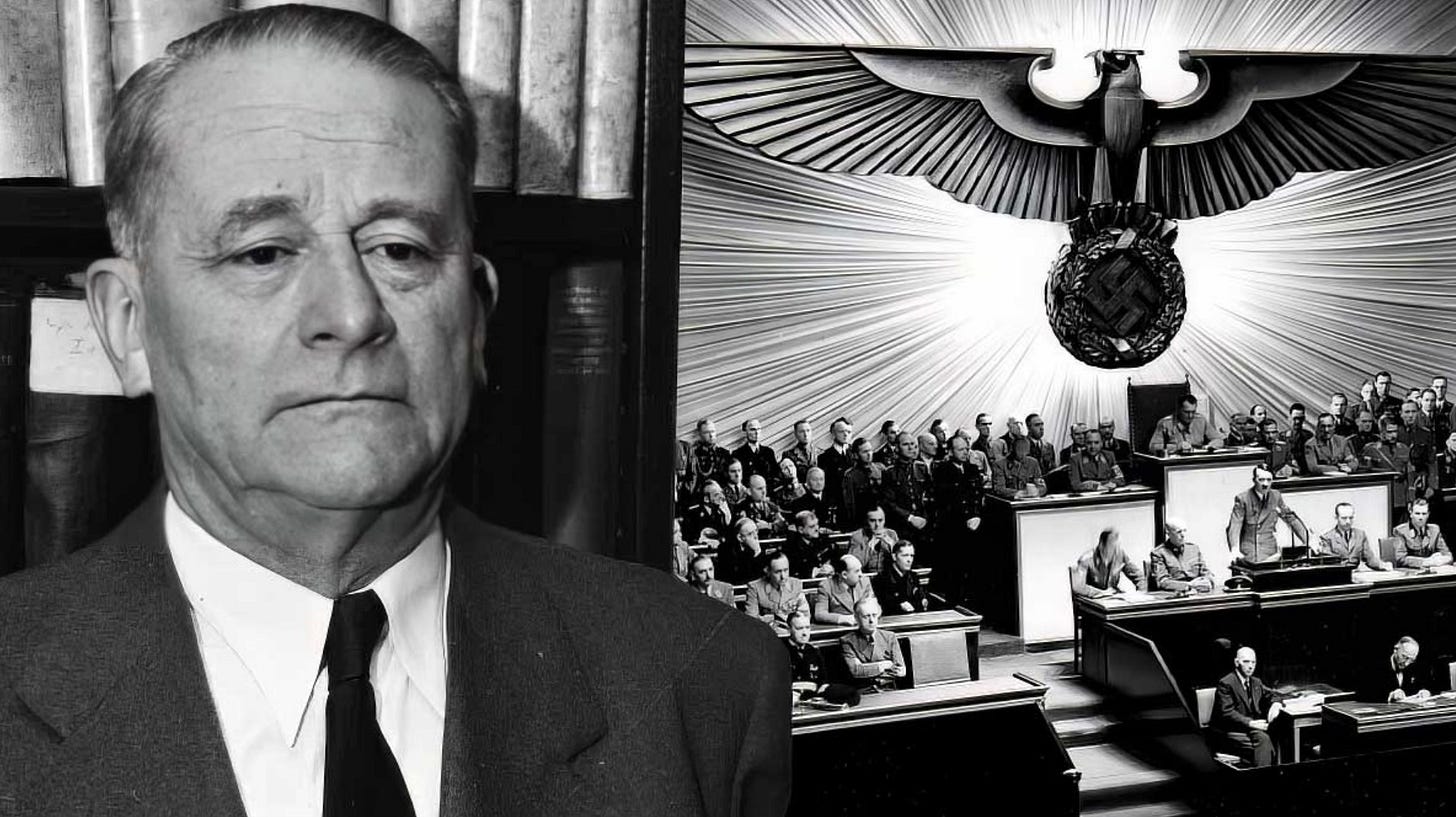

This is the world that gave us Carl Schmitt (1888–1985), a brilliant but dangerous German jurist whose ideas would echo through the twentieth century and find disturbing new life in the political turmoil of our own time. Born in the small Catholic town of Plettenberg in Westphalia, Schmitt was a conservative intellectual who witnessed the collapse of the old European order in the First World War and the fragile, contested democracy that replaced it. His work is a direct product of this crisis, an attempt to think through the limits of liberal constitutionalism when faced with what he saw as existential threats to the political community.

Schmitt argued that parliamentary democracy, with its endless debate, its culture of compromise, and its faith in rational deliberation, was fundamentally too weak to survive moments of genuine crisis. When the enemy is at the gates, whether that enemy is a foreign power, a revolutionary movement, or simply the chaos of social breakdown, the slow machinery of democratic decision-making becomes a fatal liability. In his 1922 book, Political Theology, he offered a chillingly simple definition of power that would become his most famous contribution to political thought: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception” (Schmitt, 1922). This was a statement about how power works in practice; it was a prescription, a blueprint for a new kind of politics. Schmitt was providing the intellectual toolkit for leaders to suspend the rule of law in the name of national security, to govern by decree rather than by debate, and to claim legitimacy not from the consent of the governed, but from their ability to act decisively in moments of crisis.

At the heart of this argument is the concept of the “state of exception,” a condition in which the sovereign can rule by decree, unconstrained by normal legal and constitutional limits. For Schmitt, the ability to declare such a state of emergency, to decide when the normal rules no longer apply, was the defining characteristic of sovereignty. It is in the exception, not in the routine functioning of law, that the true nature of political power reveals itself. The historical precedent is instructive. The Reichstag Fire of 1933 and the subsequent Enabling Act demonstrated precisely how Schmitt’s theory of the exception could be weaponised to transform democracy into dictatorship; a crisis, whether genuine or manufactured, that justified the suspension of civil liberties and the establishment of authoritarian rule (Notes From Plague Island, 2025b).

This idea has had a long and troubling afterlife. As the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has argued in his own work on Schmitt, the state of exception has become a normal paradigm of government in the post-9/11 era, a permanent feature of how modern states exercise power (Agamben, 2005). From the emergency powers enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic to the executive overreach seen under leaders like Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, the Schmittian exception has become a familiar, almost banal feature of modern governance (Dyzenhaus, 2006). What was once supposed to be a temporary suspension of normal politics has become the new normal.

The Friend–Enemy Distinction: Politics as War

If the state of exception is Schmitt’s theory of power, The Concept of the Political (1932) is even more stark and uncompromising. He argues that the fundamental distinction in politics is not between left and right, or between competing visions of the good society, or even between good and evil. It is, quite simply, between friend and enemy. For Schmitt, liberalism’s search for compromise, for universal values that transcend particular communities, for a politics based on rational persuasion rather than force, is a naïve and dangerous illusion that blinds us to the true nature of political life. Politics, he insists, is not a rational debate conducted in good faith by people who share a common commitment to truth and justice. It is an existential struggle for survival, a contest in which the very existence of the political community is at stake.

This friend-enemy distinction is not a metaphor or a rhetorical flourish. It is, for Schmitt, a concrete political reality, the bedrock upon which all genuine politics rests. The enemy is not a personal foe; someone you dislike or disagree with on matters of policy. The enemy is a public enemy, a collective threat to the existence and way of life of your political community. The relationship between friend and enemy is not one of debate or negotiation but of potential violence. The enemy is the one you might have to kill, and who might have to kill you, in order for your community to survive. This is politics stripped of its liberal pretensions, politics as a form of warfare by other means.

This way of thinking had a devastating impact in the twentieth century, providing a moral and intellectual justification for totalitarian regimes to treat their opponents not as political adversaries to be persuaded or outvoted, but as enemies to be eliminated. The logic of the friend-enemy distinction underpinned the Nazi extermination of the Jews, framed as the defence of the German Volk against an existential threat. It justified the Soviet purges, in which entire classes of people were designated as enemies of the revolution and liquidated accordingly. From ethnic cleansing to mass incarceration, countless acts of political violence throughout the modern era have drawn on this same intellectual foundation.

In our own time, this logic has returned with a vengeance, and it is reshaping the landscape of democratic politics in ways that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. When Donald Trump speaks of an “enemy within,” when he describes his political opponents not as fellow citizens with different views but as traitors and subversives who must be rooted out, he is invoking a Schmittian worldview (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). When Israeli politicians justify collective punishment against Palestinians as a necessary defence of the Jewish state, they are drawing on the same intellectual resource (Butler, 2020). And when the UK government frames its crackdown on protests and its “stop the boats” policy as a defence of the nation against its enemies - whether those enemies are climate activists, asylum seekers, or simply people who disagree with government policy - it is deploying the same dangerous logic.

The friend-enemy distinction has become the grammar of our polarised politics, a way of thinking that turns political disagreement into a form of warfare. It is visible in the rhetoric of culture wars, in the demonisation of immigrants and refugees, in the criminalisation of protest, and in the growing willingness of political leaders to treat democratic norms and institutions as obstacles to be overcome rather than as constraints to be respected. We are living through a Schmittian moment, even if most people have never heard of Carl Schmitt.

Subscribe to Notes From Plague Island and join our growing community of readers and thinkers.

Political Theology: When Power Wears a Halo

Schmitt’s most profound and disturbing insight may be his understanding of the relationship between politics and religion. In Political Theology, he famously claimed that “all significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularised theological concepts.” (Schmitt, 1922.) Modern political authority, even in its ostensibly secular form, retains a fundamentally theological structure. The sovereign is a kind of secular god, and the law is an article of faith rather than a product of reason. Just as divine authority is absolute and unquestionable, so too is the authority of the sovereign who decides on the exception.

This cuts against the grain of liberal political theory, which grounds authority in reason, consent, and the rule of law. For Schmitt, these are self-deceptions that obscure a deeper truth: all political order ultimately rests on a decision that cannot itself be justified by law or reason. The decision about who is sovereign, who has the authority to make and enforce the rules, is fundamentally theological. It requires an act of faith, a leap beyond reason, a willingness to submit to an authority that cannot be fully rationalised or democratised.

This fusion of the political and theological has powerful appeal for those who seek to sanctify their power. It allows them to frame their political project not as one option among many, but as a sacred duty that transcends ordinary politics. We see this today in the rise of Christian nationalism in the United States and Europe, where leaders like Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, and J.D. Vance have fused political ambition with religious mission. They present themselves as defenders of a sacred order, warriors in a cosmic battle between the faithful and the godless.

While the fusion of religion and politics is ancient, contemporary Christian nationalism is distinctively Schmittian in its rejection of liberal pluralism, its insistence that politics is fundamentally about identifying and defeating enemies, and its willingness to use state power to enforce a particular vision of the good life. This is political theology in action, and it represents a fundamental challenge to liberal democracy.

Yet Schmitt’s ideas have found an equally receptive audience in an unlikely place: Silicon Valley. Peter Thiel, the billionaire investor and co-founder of PayPal, has explicitly praised Schmitt’s critique of liberalism. In his 2009 essay ‘The Education of a Libertarian,’ published in Cato Unbound, Thiel argues that liberal democracy is in crisis and that we need to think beyond its categories (Thiel, 2009). His infamous declaration that “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible” echoes Schmitt’s own critique of liberal constitutionalism (Morozov, 2013).

For Thiel and other Silicon Valley ‘techno-authoritarians,’ Schmitt’s political theology justifies an alternative form of sovereignty. Here, the tech entrepreneur replaces the politician or priest as sovereign. The old liberal order, with its messy democratic processes, its commitment to debate and compromise, its deference to the wisdom of crowds, gives way to a new order based on algorithmic logic and CEO decisiveness. This is sovereignty reimagined for the digital age: the sovereign as coder, the exception as system override, the political community as user base. It is Schmitt translated into the language of disruption and innovation, but the underlying structure remains unchanged. Whether the sovereign wears a clerical collar or a black turtleneck, the logic is the same: all authority rests on a decision that transcends democratic accountability.

Thiel’s engagement with Schmitt runs deeper than strategic admiration. In recent years, he has delivered a series of lectures on the biblical Anti-Christ that draw heavily on Schmitt’s concept of the katechon - the restraining force that holds back the end times. This theological framework, filtered through the work of Austrian theologian Wolfgang Palaver, allows Thiel to frame democratic coordination as a manifestation of apocalyptic evil, while presenting authoritarian alternatives as necessary restraints against chaos (Notes From Plague Island, 2025). The parallel to Schmitt’s own project is unmistakable: both use crisis rhetoric and apocalyptic theology to justify dismantling democratic institutions, framing the choice as between authoritarian control and civilisational collapse.

Prophecy Fulfilled: Liberalism’s Paralysis and the Strongman’s Return

Schmitt was not just a theorist of authoritarianism; he was also a prophet of liberalism’s demise. He predicted that liberal democracy, with its endless proceduralism, its faith in rational debate, and its inability to make decisive choices in moments of crisis, would eventually collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. He foresaw a future in which the paralysis of liberal institutions would lead to a crisis of legitimacy, and in which the people, desperate for order and security, would turn to a strongman to save them. This was not wishful thinking on Schmitt’s part; he was writing in the midst of Weimar’s collapse, and he saw firsthand how the collapse of liberal democracy could pave the way for authoritarianism.

This prophecy has a chilling resonance today. We are living through what many observers have called a crisis of liberal democracy, a moment in which the institutions and norms that have sustained democratic governance for generations appear increasingly fragile and contested. The symptoms of this crisis are everywhere: declining trust in democratic institutions, rising polarisation, the erosion of shared norms, the spread of disinformation, and the rise of authoritarian populism. And in the face of this crisis, we see the return of the strongman, the leader who promises to cut through the paralysis of democratic politics and deliver results.

In the UK, the fatigue with endless Brexit negotiations and the appeal of Boris Johnson’s promise to “Get Brexit Done” can be seen as a Schmittian moment (Shipman, 2016). After years of parliamentary deadlock, of endless debates that seemed to go nowhere, of a political class that appeared incapable of making a decision and sticking to it, Johnson offered a simple message: trust me, and I will end this chaos. He presented himself as the decider, the sovereign who could cut through the Gordian knot of parliamentary procedure and deliver what the people wanted. And it worked. He won a landslide election, and he did indeed get Brexit done… though the consequences of that disastrous decision are still unfolding.

In the US, the rise of Donald Trump is another, even more striking example of the Schmittian logic at work (Snyder, 2017). Trump’s entire political persona is built on the promise of decisiveness, on the idea that he alone can fix the problems that the political establishment has failed to address. “I alone can fix it,” he declared at the 2016 Republican National Convention, a statement that could have come straight from Schmitt’s playbook. Trump presents himself as the sovereign decider, the man who is not bound by the norms and constraints that limit ordinary politicians, the leader who can act decisively in the face of crisis. And like Johnson, he has been remarkably successful in mobilising support by appealing to this Schmittian vision of politics.

Schmitt’s diagnosis of liberal weakness has been weaponised by those who seek to dismantle democracy from within. They use the language of efficiency and decisiveness to justify their attacks on democratic institutions, from the courts and the press to the electoral process itself. They frame democratic norms - the separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary, the freedom of the press - not as safeguards against tyranny but as obstacles to effective governance. The state of exception, once a temporary measure for times of genuine crisis, has become embedded in our political landscape. The strongman, once a figure of history that we thought we had left behind, has returned to the centre of the political stage.

Afterlives: Schmitt’s Rehabilitation and Rebirth

After the Second World War, Carl Schmitt was interned by the Allied authorities for his role in the Nazi regime. He had joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and served as a prominent legal theorist for the regime, providing intellectual justification for its authoritarian policies. Yet despite his deep complicity with Nazism, Schmitt was never prosecuted for war crimes. He returned to his hometown of Plettenberg, where he lived in a kind of internal exile, continuing to write and publish until his death in 1985. In the post-war years, his work was quietly rehabilitated, and he became an influential figure for a new generation of thinkers on both the left and the right.

This rehabilitation is one of the more troubling aspects of Schmitt’s legacy. How did a Nazi jurist, a man who provided intellectual cover for one of the most monstrous regimes in history, come to be treated as a serious and important political thinker? Part of the answer lies in the power of his ideas. Schmitt was a brilliant theorist whose work offers insights into the nature of political power that are difficult to dismiss, even if we find his conclusions morally repugnant. His concept of the state of exception, his critique of liberal constitutionalism, his understanding of the friend-enemy distinction - these ideas continue to illuminate the workings of modern politics, even if we reject the uses to which Schmitt himself put them.

The first strand of Schmitt’s influence runs through Leo Strauss, the German-Jewish philosopher who corresponded with Schmitt in the early 1930s before fleeing Nazi Germany. Their intellectual exchange was brief but consequential. Strauss engaged seriously with Schmitt’s critique of liberalism, even as he ultimately rejected Schmitt’s solutions. Yet Strauss’s ideas would later inspire the American neoconservative movement, and the connection is unmistakable. The neoconservative embrace of executive power, of a muscular foreign policy based on the identification of enemies, and of a scepticism toward liberal internationalism all bear traces of Schmittian thinking, filtered through Strauss’s own complex philosophical project.

A second, very different strand emerges on the left. Giorgio Agamben, the Italian philosopher, has used Schmitt’s concept of the state of exception to critique the erosion of civil liberties in the post-9/11 era. Agamben argues that the state of exception has become the dominant paradigm of contemporary governance, a permanent condition in which the suspension of law has become the norm rather than the exception. This is a left-wing appropriation of Schmitt, one that uses his insights to critique rather than to justify authoritarianism. It demonstrates that Schmitt’s ideas can be weaponised in multiple directions, which is a testament to their analytical power and their moral danger.

The third and perhaps most troubling strand runs through the new reactionary right. Nick Land, the British philosopher and theorist of the ‘Dark Enlightenment,’ draws explicitly on Schmitt’s critique of democracy in his vision of a post-democratic, techno-authoritarian future. Land and his fellow neoreactionaries argue that democracy is a failed experiment that leads inevitably to chaos and decline. What they propose instead is a return to hierarchical, authoritarian forms of governance, but reimagined for the digital age. This is Schmitt translated into the language of Silicon Valley: the sovereign not as a charismatic Führer but as an algorithm, governance not through personal authority but through code.

This brings us to Adrian Vermeule, a professor at Harvard Law School who has drawn on Schmitt in his advocacy for “common-good constitutionalism.” Vermeule’s post-liberal approach to constitutional interpretation rejects the liberal emphasis on individual rights in favour of a more communitarian, morally substantive vision of law (Vermeule, 2020). His work has been controversial, with critics arguing that it represents a dangerous turn toward authoritarianism dressed in the language of Catholic social teaching. Yet Vermeule’s project is significant precisely because it shows how Schmitt’s ideas can be adapted to contemporary American constitutional debates, providing a theoretical framework for those who seek to dismantle liberal constitutionalism from within.

What unites these disparate thinkers - from Strauss to Agamben, from Land to Vermeule- is a shared sense of disillusionment with liberal democracy. They see it as a decadent and dying order, and they are searching for a new political form to replace it. For some, like Vermeule, this means a return to a more traditional, hierarchical society in which state authority is grounded in a religious or moral vision of the common good. For others, like Land and Thiel, it means a radical break with the past, a leap into a post-human future in which the old categories of politics no longer apply. But in each case, Schmitt’s ideas provide the intellectual foundation for their critique of liberalism and their vision of what might come after. The ghost of Weimar, it turns out, has many heirs.

Why Schmitt Matters Now

Carl Schmitt is more than just a historical figure, a relic of Weimar Germany’s tragic collapse. He is a contemporary. His ideas are alive and well, and they are shaping the political struggles of our time in ways that are both visible and hidden. He offers the most coherent and powerful rationale for dismantling democracy, and his logic is everywhere, often unacknowledged and unexamined.

The global trend toward executive rule and emergency politics reveals how leaders worldwide have used crises, whether real or manufactured, to concentrate power and bypass democratic institutions. The militarisation of borders and the criminalisation of dissent show governments increasingly treating migrants, refugees, and protesters not as people with rights but as enemies to be excluded or suppressed. Meanwhile, the rise of corporate sovereignty mirrors Schmitt’s model of sovereign decisionism, as tech companies and other powerful corporations exercise a form of private authority that rivals that of states.

We have normalised the Schmittian exception. What was once supposed to be a temporary suspension of normal politics in response to a genuine emergency has become a permanent feature of how we are governed. The ‘decider’ has become the archetype of modern leadership, the model to which politicians aspire. We celebrate leaders who can get things done, who can cut through the red tape of democratic procedure, who can act decisively without being hampered by debate or dissent. But in doing so, we are embracing a vision of politics that is fundamentally at odds with democratic values.

The danger isn’t that we still read Schmitt, it’s that we’re living in the world he designed. His ideas have seeped into the groundwater of contemporary politics, shaping the way we think about power, authority, and the nature of the political even when we don’t realise it. And that is why understanding Schmitt matters. Not because we should embrace his vision - we should not - but because we need to recognise it when we see it, to understand the logic that animates it, and to resist it. The struggle for democracy in the twenty-first century is, in many ways, a struggle against the world that Carl Schmitt imagined and helped to create.

Or support us with a one-off tip → Buy Me a Coffee

References

Agamben, G. (2005) State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bendersky, J. (1983) Carl Schmitt: Theorist for the Reich. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Butler, J. (2020) The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind. London: Verso.

Dyzenhaus, D. (2006) Legality and Legitimacy: Carl Schmitt, Hans Kelsen and Hermann Heller in Weimar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kahn, P. (2011) Political Theology: Four New Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. New York: Columbia University Press.

Levitsky, S. and Ziblatt, D. (2018) How Democracies Die. New York: Crown.

Morozov, E. (2013) ‘The Rise of the Techno-Leviathans,’ The New Republic, 14 April.

Mouffe, C. (2005) On the Political. London: Routledge.

Mounk, Y. (2018) The People vs Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Muller, J.-W. (2003) A Dangerous Mind: Carl Schmitt in Post-War European Thought. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Notes From Plague Island (2025) ‘Part 9: The Billionaire Prophet: How Peter Thiel’s Apocalyptic Theology Justifies Dismantling Democracy,’ Notes From Plague Island, 4 October. Available at: https://www.plagueisland.com/p/part-9-the-billionaire-prophet-how [Accessed: 16 October 2025].

Notes From Plague Island (2025b) ‘Wake-Up Call: The Echoes of Weimar and the Fight for Democracy,’ Notes From Plague Island, 8 February. Available at: https://www.plagueisland.com/p/wake-up-call-the-echoes-of-weimar [Accessed: 16 October 2025].

Schmitt, C. (1922) Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Munich: Duncker & Humblot.

Schmitt, C. (1932) The Concept of the Political. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2007 ed.).

Shipman, T. (2016) All Out War: The Full Story of How Brexit Sank Britain’s Political Class. London: William Collins.

Snyder, T. (2017) On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. New York: Tim Duggan Books.

Thiel, P. (2009) ‘The Education of a Libertarian,’ Cato Unbound, 13 April.

Vermeule, A. (2020) ‘Beyond Originalism,’ The Atlantic, 31 March.