No Other White Faces: Robert Jenrick and the Politics of Whiteness

“I didn’t see another white face.” Robert Jenrick, 6 October 2025.

Six words that shouldn’t need explanation, yet here we are. Robert Jenrick’s remark about spending ninety minutes in Handsworth, Birmingham, without seeing “another white face” reads like something from an age we’d convinced ourselves we’d outgrown. It’s a sentence so stripped of ambiguity that the shock lies not in what he said, but in the brazenness of saying it aloud, and in the unspoken understanding that, for some, it will resonate.

For decades, British politicians have learned to code their discomfort with difference. They spoke of integration, shared values, and community cohesion. But Jenrick dispensed with euphemism. The mask slipped, and what stood beneath was as old as empire: the quiet conviction that whiteness is the baseline of belonging.

In his comments, Jenrick described visiting Handsworth in Birmingham and being struck by “the fact [he] didn’t see another white face” (Walker, 2025). He later insisted this was “not about race,” claiming instead to be highlighting “a lack of integration;” a defence as hollow as it is familiar. How can one complain of “not seeing another white face” and claim it is not about colour? Would he have felt equally unsettled had those streets been filled with white Australians, white Americans, or white South Africans? The answer, of course, is no. This is not about nationality or shared citizenship; it is about otherness.

Handsworth is not an alien landscape. It is a living piece of post-war Britain, the product of migration, labour, and resilience. According to the 2021 Census, more than 70 per cent of its residents identify as Black, Asian, or minority ethnic (Office for National Statistics, 2023). Many are descendants of those who arrived from the Caribbean and South Asia in the 1950s and 60s to rebuild a country exhausted by war. Their presence was not accidental; it was requested. To find such diversity alarming in 2025 is not a neutral observation. It is a statement of value about who counts as truly British.

What Jenrick articulated was a hierarchy of comfort: a worldview in which the sight of brown and Black Britons is still subconsciously registered as foreign. It is the language of exclusion disguised as nostalgia. And it raises an old, weary question: are we really back to this?

Whiteness as the Measure of Belonging

Robert Jenrick’s remark is fundamentally about race and power. When he spoke of not seeing “another white face,” he was expressing a sense of displacement, of something lost. But what exactly has been lost? Handsworth hasn’t changed overnight; its diversity has been part of Birmingham’s fabric for generations. What has shifted is the political mood; a growing discomfort among some with a Britain that no longer reflects their imagined past.

To describe a neighbourhood’s racial composition as a problem is to reveal what one believes to be normal. “Whiteness” becomes not merely a description but a yardstick for belonging. Scholars such as Reni Eddo-Lodge have long noted that whiteness in Britain functions as an invisible default, “a position of cultural dominance masquerading as neutrality” (Eddo-Lodge 2017). In Jenrick’s framing, the absence of whiteness becomes synonymous with the absence of Britain itself, as though Britishness begins to evaporate once the colour palette shifts.

This is why the statement is so corrosive. It does not simply describe difference; it constructs it as deficiency. The word “white” stands in for “normal,” and everything else becomes a deviation from that imagined norm. It is a quiet but profound act of exclusion; a linguistic sleight of hand that recasts a multicultural community as an aberration in need of explanation.

Britain has seen this before. When Enoch Powell warned in 1968 of “the River Tiber foaming with much blood” (Powell, 1968), he, too, dressed racial unease in the language of realism. Powell’s speech was less a prophecy than a mirror, reflecting the anxieties of a nation uncertain of its post-imperial identity. Half a century later, Jenrick’s comment draws from the same emotional reservoir: the fear that whiteness is no longer the nation’s organising principle.

But while Powell thundered from the margins, Jenrick speaks from within the political mainstream. His words reveal how easily racial nostalgia can slip back into polite conversation, reframed as concern for integration or community cohesion. Yet these are not neutral terms; they are loaded with the assumption that Britain’s diversity is a problem to be managed rather than a reality to be understood.

The subtext of Jenrick’s statement is not just discomfort with change, but a yearning for the days when the boundaries of belonging were clearer - when ‘us’ and ‘them’ were neatly divided by skin tone. It’s a nostalgia for a Britain that never truly existed outside of wartime propaganda. And it’s a nostalgia that politicians continue to weaponise because it sells. Fear always does.

Historical Context: Who Built Handsworth?

To understand Handsworth today, you have to understand what Britain once asked of it.

After the Second World War, Britain was on its knees: bombed, bankrupt, and short of labour. The newly elected Labour government under Clement Attlee turned to the Commonwealth for help. In 1948, the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury, carrying some 492 passengers from the Caribbean, among them former RAF servicemen who had fought for Britain during the war (National Archives, 2018). They were invited to fill jobs that kept the nation running - in the NHS, public transport, and industry. Soon after, workers arrived from India, Pakistan, and what was then East Africa, forming the backbone of the country’s post-war recovery.

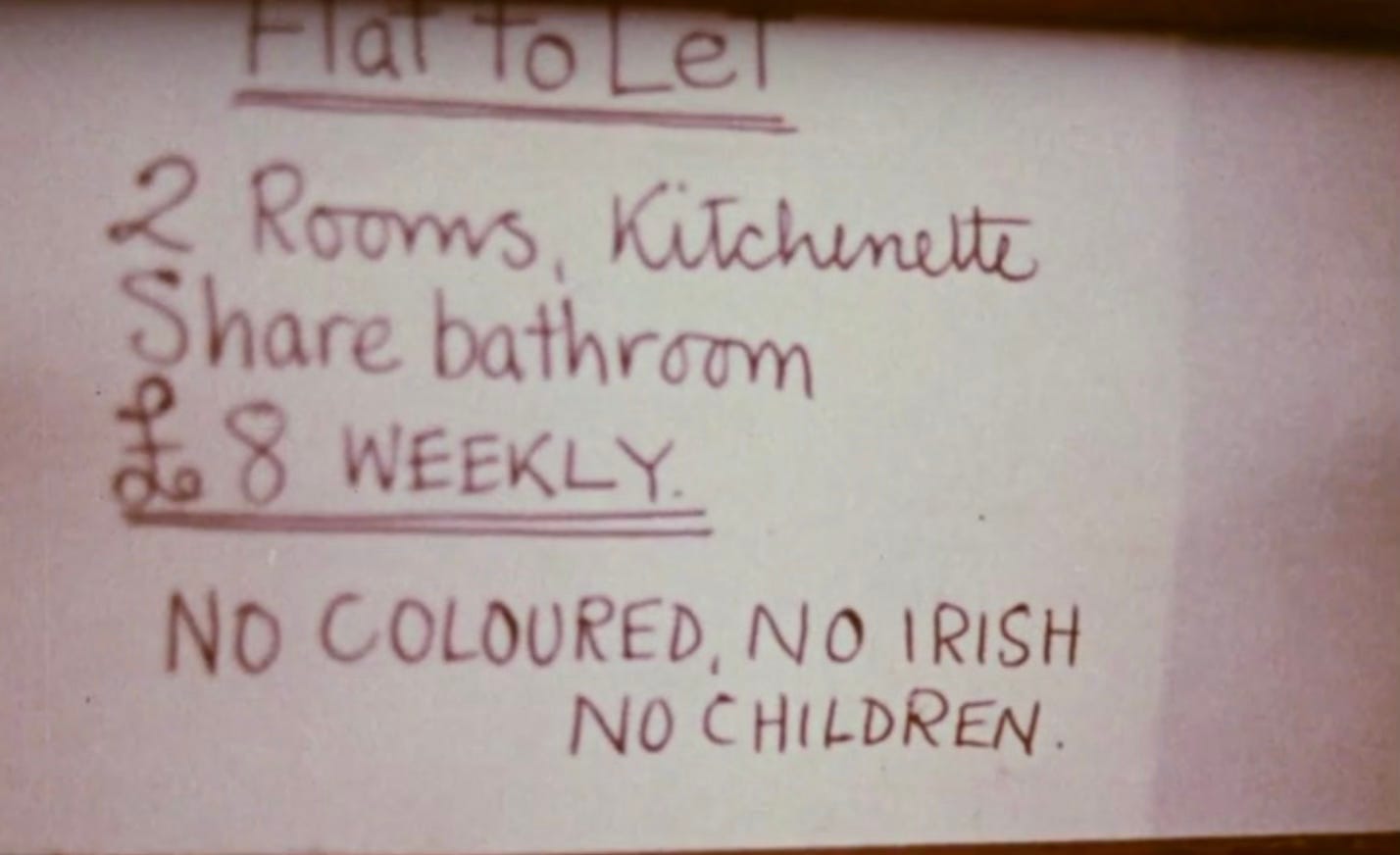

Birmingham, already an industrial powerhouse, became a magnet for this new workforce. The factories of the Midlands needed hands, and Handsworth - close to the foundries and machine shop floors - became one of the areas where Black and South Asian families settled. But their welcome was far from warm. Many landlords refused to rent properties to them; the infamous signs reading ‘No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’ appeared in boarding houses across the country (BBC News, 2018). Racism in housing meant that Black and Asian migrants were often confined to specific districts - not by choice, but by exclusion.

This is how Handsworth’s vibrant multiculturalism was born: not as a policy experiment, but as a consequence of Britain’s own prejudice.

And it was not only Black and Asian migrants who were treated as outsiders. The Irish, too - white but often Catholic, poor, and working-class - were subject to suspicion and hostility. The wrong kind of white people, you might say. The British colour line has always been flexible, stretching to include or exclude as political convenience demands.

By the 1970s and 80s, Handsworth had become a cultural hub, home to reggae musicians, poets, and political activists who gave voice to a generation that refused to be invisible. Steel Pulse, one of Birmingham’s most famous reggae bands, emerged from its streets, singing about injustice and identity. The 1985 Handsworth riots, sparked by tensions over policing and inequality, were a cry of frustration from communities who had contributed to Britain’s prosperity, but were still treated as outsiders (Fryer 1984; BBC News 2015).

To reduce this layered history to a complaint about the colour of faces on the street is to erase seventy years of labour, sacrifice, and cultural creativity. Handsworth was built by those who answered Britain’s call. Their children and grandchildren are as British as anyone born in Shropshire or Sussex. The question is not whether they belong here. It is whether Britain has ever truly accepted the gift they gave it.

The Convenient Scapegoat

When politicians like Robert Jenrick look at Handsworth and see decline, they are really looking at their own handiwork. The boarded-up shops, the overflowing bins, the eroded public realm - none of this is the fault of the people who live there. It is the direct consequence of decades of austerity, deregulation, and neglect. But it is always easier to blame faces than policies.

Birmingham’s current crisis did not appear out of nowhere. In 2023, Birmingham City Council effectively declared bankruptcy, the largest local authority collapse in British history, after years of chronic underfunding and legal mismanagement (BBC News, 2023). The city has been struggling to balance the books ever since. Bin collections have been erratic, services slashed, and entire neighbourhoods left in visible decay. When Jenrick walked through Handsworth and lamented what he saw, he wasn’t witnessing the failure of multiculturalism. He was witnessing the wreckage of his own party’s economic model.

Between 2010 and 2020, local government funding in England was cut by an estimated 40 per cent in real terms (Institute for Government, 2021). These cuts hit cities like Birmingham hardest - places with high poverty rates, larger social care burdens, and more limited reserves. Successive Conservative governments, in the name of ‘efficiency,’ shifted responsibility for essential services to councils, then stripped them of the means to provide them. The result is the visible rot of once-proud civic spaces.

When austerity erodes the state, identity politics rushes in to fill the void. The story shifts from ‘we failed to invest’ to ‘they failed to integrate.’ It’s a political sleight of hand, a redirection of anger from Westminster to the nearest convenient scapegoat. Handsworth, with its majority non-white population and stubborn pride, becomes a perfect stage set for this theatre of grievance.

It’s an old trick. Margaret Thatcher perfected it during the 1980s, when inner-city deprivation was framed not as the outcome of deindustrialisation, but as the failure of multiculturalism and moral decline. Today’s Conservatives, and increasingly the Labour Party, recycle the same logic. The result is a moral inversion: those most harmed by policy failure are recast as its cause.

The real tragedy is that this narrative works. It gives the illusion of explanation, the comfort of blame, and the false promise of restoration. If only the country could return to how it used to be. But there is no return. The world Jenrick invokes in his lament for “white faces” is gone because it never existed as he imagines it. What has really disappeared is accountability.

Subscribe to Notes From Plague Island and join our growing community of readers and thinkers.

The Summer (and Autumn) of Flagging

Just weeks before his Handsworth remarks, Robert Jenrick was photographed in Newark, smiling beneath a sea of Union flags. The former immigration minister had ordered the flags to be raised across his constituency as part of a campaign to “restore civic pride” (Sherwood 2025). The images were unmistakably symbolic. Here was a man auditioning for higher office; a politician staking his claim to represent the ‘real Britain,’ one flagpole at a time.

It was not an isolated gesture. Across the summer and early autumn of 2025, Britain entered what might be called a season of flagging - a strange performative patriotism that swept across both major parties. Kemi Badenoch opened the Conservative Party conference against a vast Union Jack backdrop. Keir Starmer, meanwhile, ensured his Labour Party rally in Liverpool was framed by military pageantry and blue-red bunting. In the absence of conviction, the flag became the message.

Jenrick’s call to hoist the flag in every civic space was presented as harmless, a bid to bring communities together. But flags rarely unite; they demarcate. They draw boundaries between those presumed to belong and those who must constantly prove that they do. In a multicultural city like Birmingham, to invoke the Union flag is not a neutral act. It carries the echo of every time ‘Britishness’ has been wielded to police difference - from Enoch Powell’s rhetoric of belonging to the ‘Rule Britannia’ nostalgia that resurged during Brexit.

As cultural historian David Olusoga has observed, “Modern Britain still hasn’t decided whether it wants to be an empire that lost its colonies, or a democracy that inherited them” (Olusoga, 2021). The flag, in this sense, has become a mirror of the national mood; brittle pride masking insecurity. When Jenrick complains about not seeing “another white face,” he’s re-asserting ownership. The flag becomes shorthand for the territory of a disappearing cultural majority.

And yet, what exactly are we being asked to salute?

Austerity-ravaged councils? Collapsing public services? Rivers thick with sewage? Wages stagnating while rents soar? The flag has become an emblem of denial, a bright distraction from the dull, relentless corrosion of daily life. It’s easier to raise a banner than to raise living standards.

Patriotism, at its best, is love of place and people, not a marketing campaign. What Jenrick and others offer is something else: a politics of anxiety dressed in red, white and blue. The more the country fragments, the more flags appear, as though fabric alone can stitch together what policy has torn apart.

The Leadership Pitch

Robert Jenrick’s “white faces” remark and his flag campaign are not disconnected moments, but two sides of the same manoeuvre. Together they form the cornerstone of a carefully crafted audition for the Conservative leadership, a contest that has already begun even if no one has yet declared it.

Jenrick’s comments are a form of political signalling, a way to announce, without saying so outright, that he understands the mood of the party’s base. The Conservatives, bruised by electoral collapse and terrified of Reform UK, are scrambling to rediscover their identity. With Nigel Farage’s movement now pulling in double-digit polling figures, the old Tory playbook of fiscal caution and managerial competence has been replaced by cultural provocation. Jenrick, like others before him, has read the moment.

The Guardian reported that his Handsworth comments were made during a fringe event at the Conservative Party Conference - the very arena where leadership bids are born (Walker 2025). In the same breath that he lamented the absence of “white faces,” he spoke about the need to defend “British values” and take back control of borders, invoking familiar Brexit-era slogans. The subtext was unmistakable: Jenrick is presenting himself as the man to reclaim the party’s soul from both liberal technocrats and Farage’s insurgency.

This is politics as performance art. The creation of a persona calibrated for a post-Johnson, post-truth era. The flag becomes the prop, the language of “integration” the script, and race the unspoken plotline. His calculation is brutally simple: there is space on the right, and he intends to fill it.

We have seen this before. When Suella Braverman positioned herself as the “anti-woke” conscience of the Conservatives, her rhetoric about multiculturalism being a “failed experiment” (Braverman 2023) drew outrage and applause in equal measure. Jenrick’s gambit is subtler but just as strategic. Where Braverman courted controversy, he projects a veneer of reasonableness - a mild-mannered technocrat lamenting social decay. Yet the destination is the same: a party defined not by policy, but by grievance.

His flag initiative in Newark was a metaphorical stake in the ground. The Telegraph described him as “a man ready to lead a patriotic renewal” (Sherwood, 2025). In Tory code, “patriotic renewal” means the reassertion of cultural control, a promise to make Britain look and feel “British” again. The danger lies in how such coded language legitimises ideas once confined to the political fringe.

It is tempting to dismiss this as posturing, but this is more than one man’s ambition. The Conservatives are redefining what counts as mainstream. When a mainstream, would-be party leader can describe a British city’s diversity as alien and be met with nods rather than condemnation, the Overton window has already shifted. Britain’s rightward drift is not being led by Nigel Farage shouting from the sidelines; it is being normalised by politicians in suits who know exactly what they’re doing.

The Far-Right Echo Chamber

This is how modern extremism grows, not in back rooms or on obscure forums, but through the amplification of ‘respectable’ voices. When a mainstream politician gives rhetorical cover to racial anxiety, it allows extremists to present their worldview as common sense. As sociologist Cynthia Miller-Idriss notes, far-right movements today depend less on formal organisation than on “cultural pipelines” that carry ideas from the mainstream to the margins and back again (Miller-Idriss, 2020). Jenrick’s remark, innocuous to some, becomes one more node in that pipeline.

Reform UK’s leader Nigel Farage seized the opportunity almost instantly. On his GB News show, he declared that Jenrick had “merely said what millions are thinking” - the oldest populist line in the book (GB News, 2025). Farage’s party has made demographic unease its lifeblood, casting immigration not as an administrative challenge but as an existential threat to British identity. By echoing their language, Jenrick blurs the line between competitor and collaborator.

The media ecosystem that feeds on outrage thrives on such moments. GB News, TalkTV, and sections of the tabloid press turn these flare-ups into week-long content cycles, reinforcing the idea that ‘ordinary Britons’ are finally ‘allowed to speak.’ Yet the effect is not liberation, but polarisation. Each repetition hardens the association between visible diversity and national decline.

What makes this feedback loop so effective is plausible deniability. Jenrick can claim he was talking about cohesion, not colour. Farage can insist he is defending free speech. Commentators can argue they are merely reporting the debate. But the result is cumulative: the racial lens becomes normal again, the vocabulary of ‘invasion’ and ‘replacement’ slips back into prime-time conversation, and the far right scarcely needs to recruit; the mainstream does the work for them.

For communities like Handsworth, the consequences are not theoretical. They live in the fallout of such narratives: spikes in hate crime, increased surveillance, a constant pressure to prove belonging. For Britain as a whole, the cost is moral. Every time a senior politician treats diversity as a curiosity or a problem, it chips away at the civic trust that holds a democracy together.

Birmingham as Symbol

If Robert Jenrick wanted to see what Britain really is, he couldn’t have chosen a better place than Birmingham. The city is a living record of everything that built this country - industry, immigration, creativity, struggle - all layered in bricks and in the accent: that soft, unhurried, musical Brummie lilt that seems to understate everything, even its own beauty. Yet to the political class, Birmingham is treated less as a city than a cautionary tale, a backdrop for moral lectures about integration and decay.

Handsworth, in particular, embodies the contradictions of modern Britain. It is where Britain’s post-war promises - equality, opportunity, belonging - were both tested and betrayed. Here, the great engines of industry once roared, drawing workers from every corner of the Commonwealth. When those engines fell silent in the 1970s and 80s, the government left communities to pick through the ruins. Unemployment soared, public housing crumbled, and police-community relations disintegrated. The 1981 and 1985 Handsworth riots were not spontaneous outbursts but symptoms of a long, festering inequality (BBC News 2015).

Yet out of that adversity, Birmingham built something remarkable. It became a cultural crucible. From Steel Pulse and UB40 to Benjamin Zephaniah, it gave Britain a sound and voice that simply could not have come from anywhere else. It’s a city that redefines Britishness daily - through language, food, music, and faith. In Handsworth today, you can walk from a gurdwara to a mosque to a church within ten minutes.

The tragedy is that this vibrancy is continually reframed as threat. To politicians like Jenrick, diversity is never a sign of success, but a symptom of disorder. Birmingham’s civic bankruptcy, its refuse-strewn streets, its strained services: all are repackaged as moral failings rather than material ones. But austerity, not immigration, bankrupted this city. When Birmingham declared itself effectively insolvent in 2023, it was not because of brown faces but because of broken politics (BBC News 2023).

There is also a cruel irony in the way politicians parachute into places like Handsworth, lament their supposed decline, and then return to Westminster having learned absolutely nothing. The litter becomes metaphor, the poverty becomes proof, the people become props. They are spoken about, rarely spoken to.

Handsworth is not evidence of Britain’s failure to integrate. It is evidence of Britain’s failure to invest. It shows what happens when a nation built on exploitation refuses to reckon with its inheritance. Yet it also stands as a rebuke to that failure, because despite everything, life continues there with astonishing resilience. The shops open. The music plays. The children walk to school in uniforms paid for by parents juggling two jobs. In that persistence lies the real British story, one that the flag-wavers and face-counters will never see.

Conclusion: The Britain We Choose to See

Robert Jenrick spent ninety minutes in Birmingham and came away with a story about colour. That tells you everything. Because the people of Handsworth don’t have the luxury of treating their neighbours as symbols in a culture war because they’re too busy getting on with life. What he mistook for decline was ordinary Britain in motion: families heading to work and school, corner shops opening for the day. The kind of quiet endurance that has always kept this country going while politicians cosplay patriotism.

The truth is simple: there is nothing wrong with Birmingham that cannot be fixed by what’s right about Birmingham. What’s broken is Britain’s politics - a machine that finds scapegoats more easily than solutions, that waves flags while bins overflow. Handsworth’s streets are not symbols of decay; they are symbols of survival. Every family, every friend, every small act of care in that community is a quiet rejection of the cynicism that governs from afar.

Jenrick’s lament about “not seeing another white face” is an admission. It tells us that for some in power, Britishness still has a colour chart. But Birmingham long ago tore up that palette. This is the city that remade itself from iron, sweat, and song. The people here don’t need to prove their belonging. They built the very ground he walked on.

So yes, raise your flags if you must. But Birmingham has already raised something stronger: its head. It doesn’t need the permission of Westminster to define what Britain is. It is Britain: stubborn, diverse, funny, imperfect, and alive.

The question now isn’t what Robert Jenrick saw when he came to Handsworth. It’s what the rest of us choose to see when we look at Britain. We can keep staring at the colour of faces, or we can face the colour of our politics.

And in Birmingham, the answer’s already clear.

We’re not going back.

References:

BBC News (2015) ‘Handsworth Riots: Thirty Years On.’ 9 September. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-birmingham-34179437 [Accessed 7 October 2025].

BBC News (2018) ‘Windrush Generation: The History of ’No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’.’ 18 April. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-43780149 [Accessed 7 October 2025].

BBC News (2023) ‘Birmingham City Council Declares Bankruptcy Over Equal Pay Claims.’ 5 September. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-birmingham-66722031 [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Braverman, S. (2023) ‘Multiculturalism has failed in Britain’, speech to the American Enterprise Institute, Washington D.C., 26 September. Transcript available at: https://www.aei.org [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Eddo-Lodge, R. (2017) Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fryer, P. (1984) Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto Press.

GB News (2025) ‘Nigel Farage: Robert Jenrick has said what millions are thinking,’ 7 October. Available at: https://www.gbnews.com [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Institute for Government (2021) ‘Local Government Funding in England.’ Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/local-government-funding-england [Accessed 7 October 2025].

National Archives (2018) ‘The Arrival of the Empire Windrush.’ Available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/empire-windrush/ [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Office for National Statistics (2023) ‘Census 2021: Ethnic group, local authorities in England and Wales.’ Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Olusoga, D. (2021) Black and British: A Forgotten History. Updated edition. London: Pan Macmillan.

Powell, E. (1968) ‘Rivers of Blood Speech’, delivered 20 April, Birmingham, United Kingdom. Transcript available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/riversofblood/zhx76g8 (Accessed 7 October 2025).

Sherwood, H. (2025) ‘Robert Jenrick orders Union flags raised across Newark to boost civic pride’, The Telegraph, 21 August. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2025/08/21/robert-jenrick-union-flags-newark/ [Accessed 7 October 2025].

Walker, P. (2025) ‘Robert Jenrick complained of not seeing another white face in Handsworth, Birmingham’, The Guardian, 6 October 2025. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2025/oct/06/robert-jenrick-complained-of-not-seeing-another-white-face-in-handsworth-birmingham [Accessed 7 October 2025].