Covid Inquiry: Johnson, Cummings, and 23,000 Reasons They Should Never Have Led Britain's Pandemic Response

There is a particular kind of agony that comes with being proven right. It is a bitter, hollow vindication, a confirmation that arrives without triumph, without relief, without anything but the cold, hard certainty that the worst was not imagined. It is the grief of knowing that your warnings went unheeded, that your fears were dismissed as hysteria, that your rage was pathologised as political opportunism. And now, years later, when the official record finally catches up with the truth you lived through, there is no satisfaction. Only the weight of all those preventable deaths, pressing down like a stone on the chest.

The damning findings of the UK Covid Inquiry land not as revelation, but as a formal, footnoted echo of a scream that has been tearing through the fabric of this nation for five long years. It is the agony of knowing that the chaos was real, the incompetence was lethal, and the suffering was, in so many thousands of cases, entirely avoidable. The Inquiry, chaired by retired judge Heather Hallett, has produced more than 750 pages across two volumes documenting what millions of us already lived through: a government of unserious men, a nation ruled by chaos, and a public gaslit into believing that their leaders were doing everything they could.

We were told, over and over, in the face of all evidence, a simple, soothing lie: “Boris is doing his best.” It was a phrase that became a mantra, a shield, a sedative. It was deployed by ministers on morning television, by backbenchers in Parliament, by columnists in the right-wing press. It was used to shame dissenters, to pathologise critics, to silence the rage of those who watched their loved ones die through a screen, alone and afraid. To question whether Boris was, in fact, doing his best was to be unpatriotic, unkind, unreasonable. It was to be the sort of person who kicks a man when he is down, who plays politics with a pandemic, who cannot see that we are all in this together.

The Inquiry, in its 750 pages of meticulous, devastating detail, has stripped that euphemism bare. It has shown us what “doing his best” truly meant. It meant a Prime Minister on holiday while a pandemic gathered pace. It meant a government that actively cultivated a “toxic and chaotic” culture at the heart of the state. It meant decisions made on gut instinct and personality politics rather than evidence and expertise. It meant that 23,000 people died in the first wave alone who did not have to die. We were not cynics. We were witnesses. And now, at last, the official record has caught up with what we saw.

The Inquiry’s Verdict: A Circus of Failure

The Inquiry’s overall verdict is as succinct as it is brutal: the UK’s response to Covid was “too little, too late” (Walker and Murray, 2025a). The phrase appears repeatedly throughout the report, a refrain that captures the essence of a government that was always behind the curve, always reacting rather than anticipating, always choosing delay over decisiveness. But this was not a passive failure of a system overwhelmed by an unprecedented crisis. It was an active failure of leadership, a direct consequence of the character of the man at the top and the culture he created around him.

The Inquiry does not separate the institutional collapse from the personal failings of Boris Johnson; it shows, with chilling clarity, that the former was a product of the latter. The circus at the centre of government was not an unfortunate byproduct of a crisis; it was the crisis itself. A functioning state requires clear lines of authority, competent crisis management, and leaders who take their responsibilities seriously. The UK had none of these things. What it had instead was Boris Johnson.

February 2020 was, in the Inquiry’s own words, “a lost month” (Walker and Murray, 2025a). As the virus tore through Italy, as hospitals in Lombardy became overwhelmed, as the world began to grasp the scale of the coming catastrophe, the British state was rudderless. Johnson did not chair a single COBRA meeting before March, despite this being the most serious public health emergency in a century. The Inquiry notes that while there is nothing to mandate that COBRA is always chaired by a Prime Minister, it was “surprising” that Johnson did not do this before March - a piece of British understatement that barely conceals the scale of the failure (Walker and Murray, 2025a).

The response to the pandemic “essentially halted” during the February half-term holiday week. And where was the Prime Minister during this critical period? He was at Chevening, the government’s grace-and-favour country retreat in Kent, a place where Prime Ministers traditionally go to relax and escape the pressures of office. The Inquiry notes, with a politeness that only amplifies the horror, that “it does not appear that he was briefed, at all or to any significant extent, on Covid-19 and he received no daily updates” (Walker and Murray, 2025a).

Let that sink in. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, in the middle of a global pandemic that was already killing thousands in Europe, spent an entire week on holiday without being briefed on the crisis. He was on holiday. The virus was not. While he relaxed at Chevening, the virus was spreading through British communities, undetected and unchecked because the government had failed to implement any meaningful testing regime.

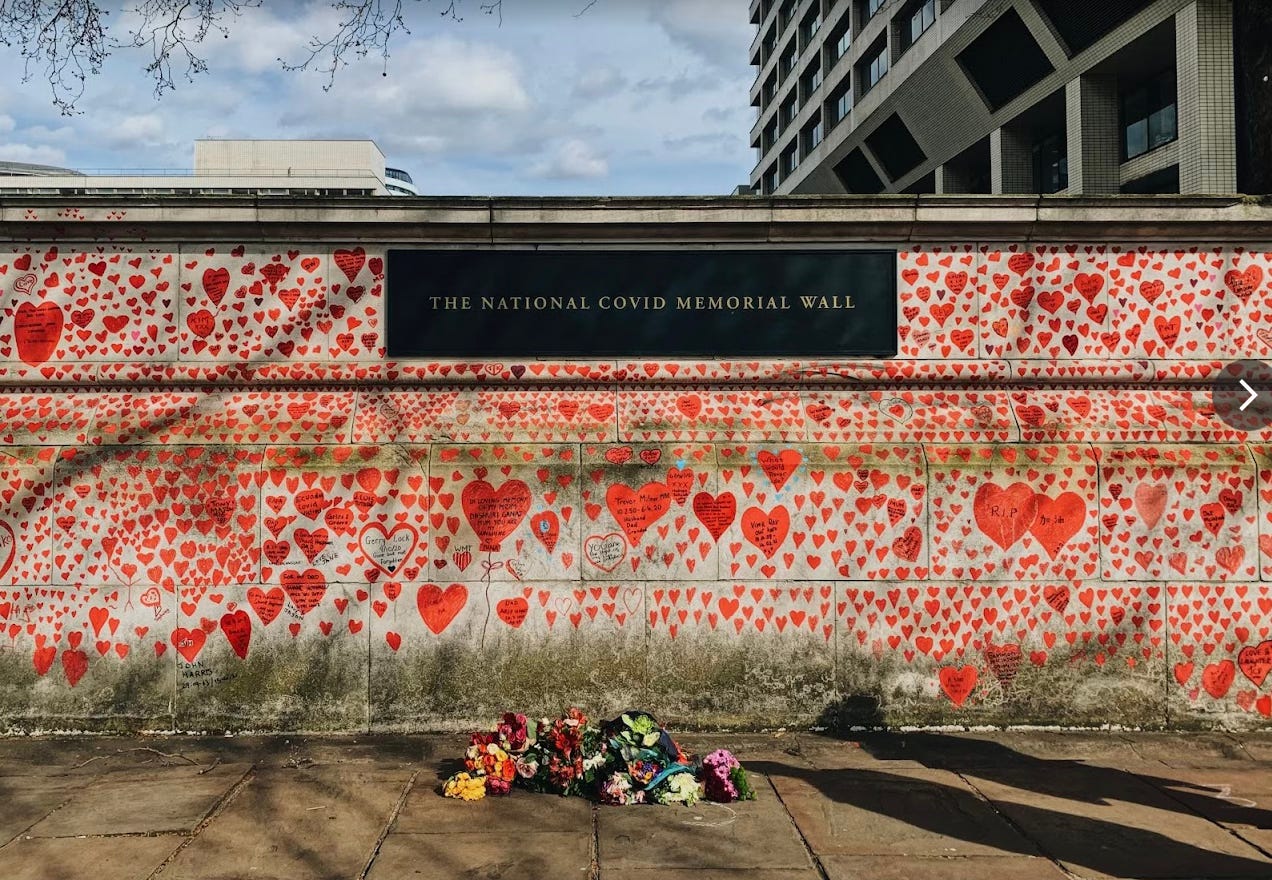

This dereliction had a direct, quantifiable cost. The Inquiry’s modelling suggests that if lockdown had been imposed on 16 March, a week earlier than it was, 23,000 lives could have been saved in England in the first wave alone (Walker and Murray, 2025a). Not an abstract “many lives” or “significant loss.” 23,000 specific, individual human beings. It is a stadium full of people. It is a town. It is 23,000 funerals that never happened, 23,000 empty chairs at Christmas, 23,000 voices we will never hear again, 23,000 families torn apart by grief that was, according to the official inquiry, avoidable.

By the second week of March, the situation was, in the Inquiry’s words, “little short of calamitous” (Walker and Murray, 2025a). There was no proper plan, no testing taking place, and thus no understanding of how far the virus had spread through the population. The government was flying blind, and it was flying blind by choice. The capacity for testing existed; it was simply not deployed. The expertise existed; it was simply not listened to. And still, Johnson dithered. He was, as the Inquiry puts it, “acting in accordance with his own optimistic disposition” (Walker and Murray, 2025a), a man who believed he could charm a virus into submission, who thought that British exceptionalism and a bit of Churchillian bluster would see us through.

Even after the lockdown was finally imposed on 23 March, the mistakes continued. The Inquiry notes that the exit from restrictions in the summer of 2020 was “unwise,” pushed in part by Rishi Sunak, the then Chancellor, who was more concerned with the economy than with public health (Walker and Murray, 2025a). This is the man who has spent years cultivating an image of sober, sensible competence, the technocrat who understands spreadsheets and fiscal responsibility. The Inquiry reveals him as just another cheerleader for a policy of reckless endangerment, a man who prioritised the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme over the lives it would cost.

The failures of the first wave effectively served as a blueprint. The Inquiry details how Johnson’s “oscillation” - the very shopping-trolley indecisiveness that we wrote about in real time, that Dominic Cummings himself described with contempt (L&A, 2025) - made decisions slow and inconsistent throughout the pandemic. In the autumn of 2020, as the second wave grew, “Mr Johnson repeatedly changed his mind on whether to introduce tougher restrictions and failed to make timely decisions” (Walker and Murray, 2025a).

The Inquiry documents how Johnson rejected advice for a “circuit breaker” lockdown (a short, sharp intervention that could have prevented the worst of the second wave) until it was too late. His oscillation enabled the virus to “continue spreading at pace” and ultimately resulted in a longer, more painful lockdown from 5 November 2020 (Walker and Murray, 2025a). This was, in the Inquiry’s damning assessment, “inexcusable” (Walker and Murray, 2025a). The government had all the information it needed. It had seen what happened in the first wave. It knew the cost of delay. And it delayed anyway.

All four UK governments - England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland - made the same mistake over Christmas 2020, saying that restrictions could ease for the holiday period, giving people “false hope” even as a new, more infectious variant was spreading rapidly (Walker and Murray, 2025a). Rather than governance, this was wishful thinking dressed up as policy, a collective delusion that we could have a normal Christmas if we just believed hard enough.

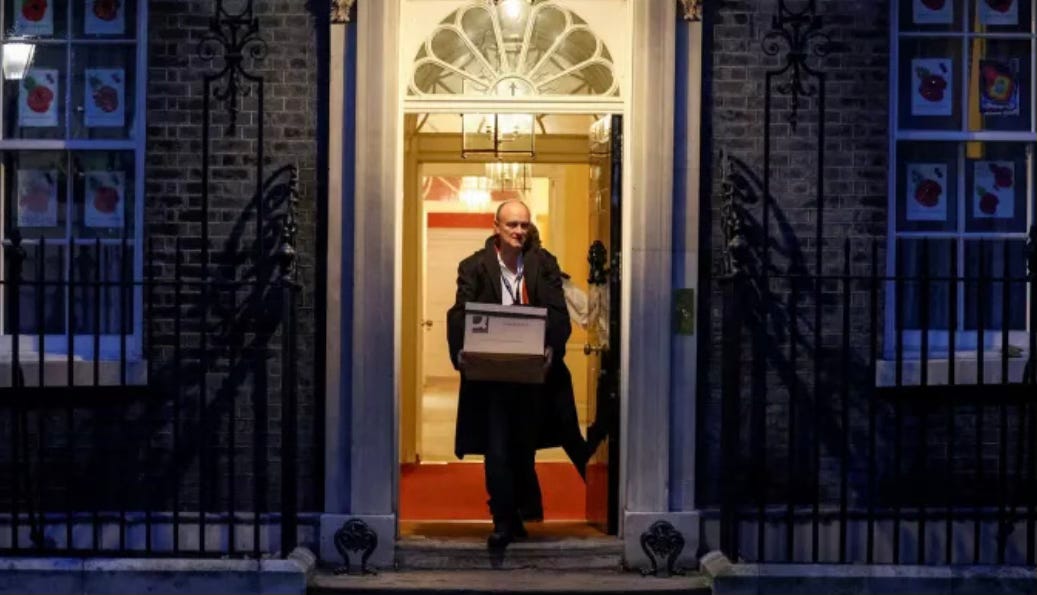

Dominic Cummings: The Bastard in the Room

If Johnson was the ringmaster of this circus of failure, Dominic Cummings was its chief architect of chaos. We have called him a bastard before, and we will do so again. It is the only word that adequately captures the particular combination of intelligence, cruelty, and contempt for democratic norms that Cummings brought to the heart of government. The Inquiry, in its own way, has now done the same. It paints a portrait of a man who “poisoned the atmosphere” of Downing Street, who “strayed far from the proper role of a special adviser,” and who made “key decisions in 10 Downing Street which were for the prime minister to make” (Walker and Murray, 2025b).

This was not a rogue actor operating against the wishes of his boss. It was, the Inquiry makes clear, “an arrangement with which, it must be acknowledged, Mr Johnson was content” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). Johnson did not just tolerate Cummings; he enabled him. He gave him power without accountability, influence without responsibility. He allowed an unelected adviser to run roughshod over ministers, civil servants, and democratic process itself. And when the consequences of that decision became clear, when the toxic culture began to affect the quality of decision-making during the worst public health crisis in a century, Johnson did nothing.

Cummings, the Inquiry finds, “materially contributed to the toxic and sexist workplace culture at the heart of the UK government,” using “offensive, sexualised and misogynistic language” to create a “culture of fear, mutual suspicion and distrust” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). The report documents how this culture affected everyone who worked in Downing Street during the pandemic. Civil servants were afraid to speak up. Experts were sidelined. Women, in particular, found their voices ignored in a “macho” environment where the loudest, most aggressive voices prevailed (Walker and Murray, 2025b).

This was bullying as a form of governance. And it had a direct impact on the quality of decision-making. Those at the centre of the crisis were “working under significant psychological stress and pressure,” and as a result of the poor culture, “the quality of advice and decision-making suffered” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). When people are afraid, they tend not to give their best advice, challenge bad decisions, or speak truth to power. They keep their heads down and hope to survive. This is how disasters happen.

The Inquiry is clear that Cummings, “notwithstanding his undoubted ability and the fact that he had many qualities useful to a prime minister,” was “a destabilising influence” whose behaviour “contributed significantly to a culture of fear, mutual suspicion and distrust that poisoned the atmosphere in 10 Downing Street and undermined the authority of the prime minister” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). Read that sentence again. An official inquiry has found that the Prime Minister’s chief adviser undermined the authority of the Prime Minister. This is not normal. This is not how government is supposed to work.

But this was not a bug; it was a feature. The Inquiry confirms that Johnson “intentionally sought to foster conflict and a chaotic working environment,” believing it created healthy debate (Walker and Murray, 2025b). He did not seek to “restrain or control Mr Cummings,” nor did he “exercise proper leadership in rectifying the toxic and chaotic culture” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). He actively encouraged it. He wanted the chaos. He wanted the fear. He wanted a court of terrified sycophants, and in Cummings, he found his ideal courtier. Johnson only acted when the pair fell out irreconcilably in November 2020 and Cummings left his job - not because the culture was wrong, but because it had become personally inconvenient.

In response to the Inquiry’s findings, Cummings did what he always does: he attacked. He claimed the Inquiry had “enabled a vast rewriting of history” and that the experts were “completely wrong” in the first quarter of 2020, advising the government “to do almost nothing” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). This is the Cummings playbook: deflect, deny, and never, ever accept responsibility. He rewrites history in real time, then accuses others of rewriting it. The Inquiry has his number. We have always had his number. As we wrote in our analysis of Cummings as the Proto-Miller of Whitehall, he is not a populist; he is “a techno-authoritarian engineer who dreams of replacing democratic process with algorithmic obedience” (L&A, 2025). He does not believe in movements; he believes in leverage. And he is still looking for his next host.

The Culture of Fear: A Tale of Two Britains

The culture of fear that Cummings cultivated did not stay within the walls of No. 10. It radiated outward, touching every life in Britain. But it created two different Britains, two different experiences of fear. Inside government, it was the fear of a bully, the fear of losing your job, the fear of being on the wrong side of a WhatsApp message, the fear of speaking up when you knew something was wrong. Outside, it was the fear of death.

While civil servants were being bullied and experts sidelined, the public lived in a state of profound, existential dread. We lived in isolation, cut off from the people we loved, unsure if we would ever see them again. We grieved alone, unable to hold the hands of the dying, unable to gather together to mourn. We attended funerals over FaceTime, watching on a screen as coffins were lowered into the ground, the priest’s voice breaking up over a bad connection. We watched our children’s childhoods shrink to the size of a screen, their friends reduced to faces in Zoom boxes, their education a pale shadow of what it should have been.

We gave birth alone, without our partners, without our mothers, bringing new life into the world in a state of terror and isolation. We waved at our grandparents through windows, their faces a blur of love and confusion, their hands pressed against the glass. We watched them fade, week by week, the isolation eating away at them as surely as any virus. We made impossible choices: risk infection to see a dying parent or stay away and live with the guilt forever. The Inquiry documents the institutional fear; we lived the human fear. The two are inextricably linked. A government that runs on fear cannot govern with compassion.

Gaslighting as Governance

And all the while, we were told: “Boris is doing his best.” This is what gaslighting sounds like when it is spoken by an entire state apparatus. It is the systematic denial of a reality that is staring you in the face. It is being told that what you are seeing is not real, that what you are feeling is not valid, that your concerns are not legitimate. It is being told that you are the problem, not the government that is failing you.

We were told that the delays were necessary, that they were based on science, that the government was following expert advice. The Inquiry reveals this was a lie. The concept of “behavioural fatigue,” the idea that the public would not tolerate a long lockdown and would stop complying with restrictions after a certain period, was used as a key justification for delaying the first lockdown. The Inquiry found that this concept “had no grounding in behavioural science and proved damaging, given the imperative to act more decisively and sooner” (Walker and Murray, 2025a).

The science was invented to justify political cowardice. Chris Whitty and Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief medical and scientific advisers, warned about behavioural fatigue, and the government used this warning as an excuse to delay. But the concept was baseless. There was no evidence for it. It was a theory plucked from thin air, dressed up in scientific language, and used to justify a decision that would cost 23,000 lives. This is gaslighting at the highest level: telling the public that the government’s inaction is based on science when the science does not exist.

We were told to follow the rules, while they broke them. The Inquiry notes that the rule-breaking by Johnson and his advisers, most infamously Cummings’s trip to Barnard Castle to “test his eyesight,” “undermined public confidence in decision-making and significantly increased the risk of the public failing to adhere to measures designed to protect the population” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). This was as hypocritical as it was dangerous, and it cost lives. When the public sees their leaders breaking the rules, they lose faith in the rules themselves. They start to think: if it is not serious enough for them to follow the rules, why should I?

The Inquiry is clear on this point: “It is vital during an emergency that those in positions of leadership follow the public health rules that they require the public to observe. They must also deal swiftly and decisively with any instances of alleged rule-breaking among their ministers and advisers to ensure public confidence in the response is maintained” (Walker and Murray, 2025b). Johnson did neither. He broke the rules himself, attending parties in Downing Street while the rest of us were forbidden from seeing our families. And when Cummings broke the rules, Johnson defended him, standing by him even as public trust collapsed.

This was the ultimate act of gaslighting: to demand sacrifice from a nation while treating the rules as optional for themselves. To tell us that we were all in this together while making it clear that some of us were more in it than others. To ask us to trust the government while demonstrating, over and over, that the government did not trust us enough to tell us the truth.

The Pain of Vindication

The Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK group, who fought so hard for this Inquiry, who refused to let the government move on and forget, who kept the pressure on even when they were exhausted and grief-stricken, said in their statement: “While it is vindicating to see Boris Johnson blamed in black and white for the catastrophic mishandling of the pandemic, it is devastating to think of the lives that could have been saved under a different prime minister” (Walker and Murray, 2025a).

This is the heart of the matter. The pain of vindication. The agony of being proven right. For five years, these families have been told they were wrong, that they were politicising their grief, that they should move on, that they should stop dwelling on the past. They have been told that the government did everything it could, that no one could have predicted how bad it would be, that mistakes were made but lessons have been learned. They have been gaslit by the state, by the media, by people who should have known better.

Now, in the cold, formal language of a 750-page report, they have been told what they already felt in their bones: that their loved ones died because the government waited too long, because the Prime Minister was on holiday, because the man advising him was a bully, because the entire system was rotten to the core. The Inquiry calls it “avoidable loss.” We call it our mothers, our fathers, our friends. We call it by their names, because they were not statistics. They were people. They had lives, families, futures. And they were taken from us by a government that could not be bothered to do its job.

There is no triumph in this vindication. There is only the weight of all those preventable deaths, the knowledge that it did not have to be this way, the rage at a system that failed so completely and has faced so few consequences. The bereaved families have been proven right, but their loved ones are still dead. The Inquiry has told the truth, but the truth cannot bring anyone back.

The Most Horrifying Question: Why Are These People Still Circling Power?

Perhaps the most horrifying part of this story is that it is not over. The architects of this catastrophe are not disgraced in exile. They are circling power, waiting for their chance to return, or in some cases, already back in positions of influence. Johnson remains a media creature, rehabilitated by the same right-wing press that enabled his lies, writing columns and giving speeches and being treated as a serious political figure rather than a man whose incompetence killed thousands.

Cummings, that bastard who poisoned the well, is now positioning himself as a kingmaker for Reform UK, whispering sweet nothings into the ear of Nigel Farage, offering his services as the man who can turn a populist movement into a functioning government (L&A, 2025). He sees human beings as interchangeable delivery systems for his vision. Johnson was a vessel. Gove was a prototype. Vote Leave was a launchpad. Now Reform UK is starting to look like a fresh incubator, and Cummings is hovering at the edges, offering his expertise in chaos, his talent for destruction.

Why is there no political death for men who presided over a national tragedy? Why is the same media ecosystem that enabled the catastrophe now regrouping to give them a second act? These are the questions that should haunt us. In a functioning democracy, the kind of failures documented in the Inquiry would end careers permanently. There would be consequences. There would be accountability. But we do not live in a functioning democracy. We live in a system where failure is rewarded, where incompetence is excused, where the same people cycle through power regardless of how much damage they do.

The Inquiry has also revealed uncomfortable truths about the continuity of failure at the institutional level. Chris Wormald, who was the head civil servant at the Department of Health during the pandemic, is now Keir Starmer’s cabinet secretary, the most senior civil servant in the government. The Inquiry found that Wormald failed to correct Matt Hancock’s “over-enthusiastic impression” of the department’s work and failed to properly investigate widespread doubts about Hancock’s effectiveness (Walker and Murray, 2025a). This is the man now running the civil service. The continuity of failure is institutional. The rot is deep, and it is still there.

Conclusion: The Reckoning Still Hasn’t Happened

The Inquiry has told the truth. It has done so in meticulous, devastating detail, in 750 pages that will stand as the official record of one of the greatest peacetime failures in British history. But truth without consequences is just documentation. It is a 750-page footnote to a mass grave. It is a monument to failure without any mechanism for accountability. What do we do with this knowledge? What does accountability look like in a nation that moves on before the dead are buried?

It looks like remembering. It looks like refusing to be gaslit. It looks like holding the record, because someone must. The Inquiry has given us the truth, but it cannot give us justice. Justice would require consequences. It would require that the people responsible for this catastrophe face some kind of reckoning, that they are barred from public life, that they are held accountable in a meaningful way. But that is not going to happen. Johnson will continue to write his columns, and Cummings will continue to plot his return. Wormald will continue to run the civil service.

We were told, for so long, that Boris was doing his best. The Inquiry has freed us from that lie. It has shown us, in black and white, that he was not doing his best. He was not even doing the minimum. He was on holiday while the virus spread. He was oscillating while people died. He was actively encouraging a toxic culture that made good decision-making impossible. But being freed from the lie does not free us from the consequences of the lie. The dead are still dead. The grief is still raw. And the men who did this are still here.

We remember, and we won’t be gaslit. We will keep the record, because someone must. And when they try to return to power - when the bastards come knocking again - we will be here, holding up the mirror they refuse to look into. The Inquiry has given us the truth. Now we must decide what to do with it. The reckoning still hasn’t happened, but it must. If there are no consequences for failure on this scale, then we are not a democracy. We are just a nation waiting for the next catastrophe, the next set of unserious men, the next round of bodies piling high.

The next time they tell us that everything is fine, that they are doing their best, that we should trust them, we will know better. We have the receipts. We have the Inquiry. We have the truth. And we will not let them forget it.

References

L&A (2021a) ‘We’re No.1!’, Notes From Plague Island, 19 January. Available at: https://www.plagueisland.com/p/were-no-1 [Accessed: 21 November 2025].

L&A (2021b) ‘... And You Will Know Us by the Trail of the Dead’, Notes From Plague Island, 26 April. Available at: https://www.plagueisland.com/p/and-you-will-know-us-by-the-trail-of-the-dead [Accessed: 21 November 2025].

L&A (2025) ‘Part 12: The Proto-Miller of Whitehall: Dominic Cummings, Farage, and the Long War to Rewire Britain’, Notes From Plague Island, 19 October. Available at: https://www.plagueisland.com/p/part-12-the-proto-miller-of-whitehall[Accessed: 21 November 2025].

Walker, P. and Murray, J. (2025a) ‘”Too little, too late”: damning report condemns UK’s Covid response’, The Guardian, 20 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2025/nov/20/too-little-too-late-damning-report-condemns-uk-covid-response [Accessed: 21 November 2025].

Walker, P. and Murray, J. (2025b) ‘Dominic Cummings “poisoned the atmosphere” of Boris Johnson’s No 10, Covid inquiry finds’, The Guardian, 20 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2025/nov/20/dominic-cummings-boris-johnson-no-10-culture-covid-inquiry [Accessed: 21 November 2025]